Key signatures in music define the set of sharps or flats used in a piece, indicating the tonality or ‘key’ of the music. They simplify notation, providing essential context for interpreting melodies and harmonies.

Introduction

From songwriters to composers to those just starting their musical journey, understanding the fundamental elements of music theory is key (pun intended!) to unlocking the vast world of music composition. One such crucial component is the concept of key signatures in music.

What are Key signatures? They might appear as just a group of sharps or flats at the start of a piece of music, but they hold a profound role in defining the tonal landscape of a composition. They are the shorthand to an unspoken rule, a guide to the harmonic fabric of a piece, setting the stage for the melodies and harmonies that are about to follow.

In this article we will delve into key signatures, their relationship with scales, how to read them, and much more. Whether you’re writing your first song or aiming to gain a deeper understanding of how your favorite pieces of music are constructed, a solid grasp of key signatures will surely prove invaluable.

Just as our earlier articles provided a firm grounding in musical concepts like pitch, tone, intervals, scales, and the key in music, this exploration of key signatures will further enhance your music theory knowledge and fuel your musical creativity.

Understanding Key Signatures

Music is a language of its own, and just like any language, it has its alphabet and grammar rules that allow us to read and understand it. In music notation, key signatures serve a similar purpose. They form a crucial part of the grammar of music, providing essential information about the “key” of the piece.

But what is a key signature? It’s a set of sharps or flats placed on the staff at the beginning of a piece of music, immediately after the clef. It denotes which pitches should be played as sharp (raised in pitch) or flat (lowered in pitch) for the piece’s duration or until another key signature is introduced.

The number and order of these sharps or flats can tell you the piece’s key. But it’s important to note that understanding the key of a piece is not just about knowing the name of the key but understanding the tonal center of the music and the specific pattern of whole steps and half steps that define its major or minor scale.

Purpose and Function of Key Signatures

The purpose of a key signature in music is twofold: it simplifies the written music and sets the tonality of the piece.

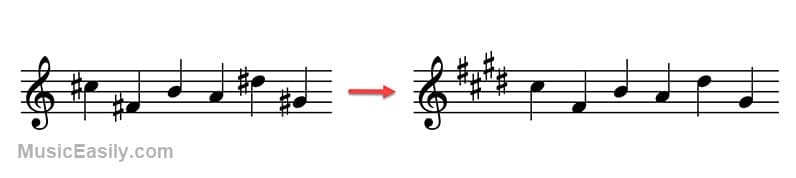

When composing or performing music, certain pitches might consistently need to be altered. Instead of writing these alterations (accidentals) in front of each note, a key signature allows the composer to indicate at the start which notes should be consistently played as sharped or flatted.

This simplification streamlines the music notation, making the sheet music easier to read and play. Our previous post on “What are Accidentals in Music?” explains this process.

Furthermore, key signatures provide clues about the tonality of the piece. Essentially, they help indicate the “home base” or the main pitch around which the music revolves.

This tonal center, which we discussed in our blog post on “What is a Key in Music?” gives the music a sense of direction and purpose. It’s the note that the music often starts and ends on and to which it feels most resolved when returning.

In the context of our topic, a key signature informs us about the set of notes that the music will most frequently use, thus indicating the key of the piece. This key, in turn, will significantly impact the mood and feel of the music, whether it’s the brightness of a major key or the somber tone of a minor key.

Key vs Key Signature

A “key” in music refers to the tonal center or the main pitch around which a piece of music is based, thereby establishing the tonality of the piece.

On the other hand, a “key signature” is a visual representation that indicates the key of a piece, effectively setting the tonality for the written music by instructing which notes to alter in pitch consistently throughout the piece.

This distinction is vital because it allows us to separate the conceptual framework of musical composition (the key) from the practical notation tools used to represent this framework in written music (the key signature).

Key Signatures and Scales

Key signatures are intimately tied to scales, those ordered sequences of pitches that serve as the building blocks of music. If you’ve read our blog post on “What is a Musical Scale?” you’ll know that scales provide a structure to the melody and harmony of a piece. Key signatures serve as a kind of shorthand notation for these scales.

So, how do key signatures relate to scales? The sharps or flats in the key signature correspond to the pitches altered in the scale. In other words, if a note is sharpened or flattened in the scale, it will appear as such in the key signature.

This makes it clear which notes should be raised or lowered when playing the piece without having to mark every single altered note.

Major Key Signatures

Every major scale has its unique key signature. These major key signatures can include sharps or flats, depending on the specific sequence of whole and half steps that define the major scale.

It’s helpful to know the specific sequence of sharps or flats that define each one to understand major key signatures. For instance, the key of G major has one sharp (F#), the key of D major has two sharps (F#, C#), and so on. This pattern follows the Circle of Fifths, which further expands our understanding of the relationship between keys.

The key of C major is unique because it has no sharps or flats. It’s often the first key signature beginners learn because the white keys on a piano represent it.

| Major Key | Number of Sharps | Sharped Notes |

|---|---|---|

| C Major | 0 | – |

| G Major | 1 | F# |

| D Major | 2 | F#, C# |

| A Major | 3 | F#, C#, G# |

| E Major | 4 | F#, C#, G#, D# |

| B Major | 5 | F#, C#, G#, D#, A# |

| F# Major | 6 | F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E# |

| C# Major | 7 | F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, B# |

| Major Key | Number of Flats | Flatted Notes |

|---|---|---|

| C Major | 0 | – |

| F Major | 1 | Bb |

| Bb Major | 2 | Bb, Eb |

| Eb Major | 3 | Bb, Eb, Ab |

| Ab Major | 4 | Bb, Eb, Ab, Db |

| Db Major | 5 | Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb |

| Gb Major | 6 | Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb |

| Cb Major | 7 | Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb, Fb |

Minor Key Signatures

Like each major scale, every minor scale also has its key signature. The key signature of a minor key is defined by the specific sequence of whole and half steps that form its scale.

One intriguing aspect of minor keys is the concept of relative keys. Every major key has a relative minor key with the same key signature. For example, the key of A minor is the relative minor of C major because both share the same key signature – no sharps or flats. The only difference is the tonic or the “home” note.

Understanding the relationship between key signatures and scales – both major and minor – not only helps us to read and write music more effectively but also enriches our understanding of music’s tonal structure. By knowing the key signature, we can understand the tonal landscape the composer is working within, thus enhancing our appreciation of the music.

| Minor Key | Number of Sharps | Sharped Notes |

|---|---|---|

| A minor | 0 | – |

| E minor | 1 | F# |

| B minor | 2 | F#, C# |

| F# minor | 3 | F#, C#, G# |

| C# minor | 4 | F#, C#, G#, D# |

| G# minor | 5 | F#, C#, G#, D#, A# |

| D# minor | 6 | F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E# |

| A# minor | 7 | F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, B# |

| Minor Key | Number of Flats | Flatted Notes |

|---|---|---|

| A minor | 0 | – |

| D minor | 1 | Bb |

| G minor | 2 | Bb, Eb |

| C minor | 3 | Bb, Eb, Ab |

| F minor | 4 | Bb, Eb, Ab, Db |

| Bb minor | 5 | Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb |

| Eb minor | 6 | Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb |

| Ab minor | 7 | Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb, Fb |

Reading Key Signatures

Recognizing and understanding key signatures is a vital part of reading music. When looking at sheet music, you’ll often notice a group of sharps or flats at the beginning of each line just after the clef sign – the key signature. They tell us the piece’s key and guide us on which notes to play sharp or flat throughout the piece.

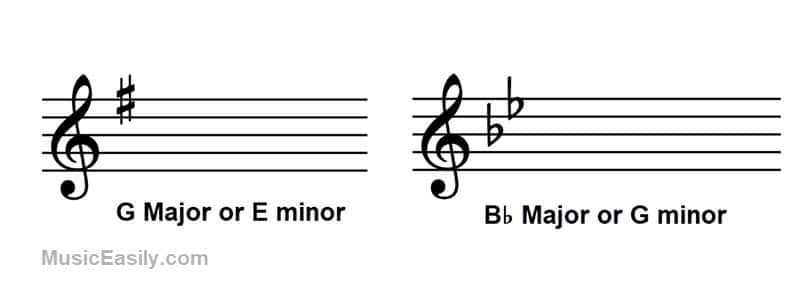

The key signature is found directly after the clef and before the time signature. The sharps or flats (collectively known as accidentals) appear on the specific lines and spaces corresponding to the notes they affect. To find out which key a piece of music is in, you need to look at the number and type of accidentals in the key signature and a few other musical hints.

For instance, if you see no sharps or flats after the clef, you’re likely in the key of C Major or A minor. If there’s one sharp (F#), the piece is likely in G Major or E minor.

Remember, though, that it’s not always this straightforward; the key might change throughout the piece, and some pieces may use modes (like Dorian or Mixolydian) or other scales outside of the traditional major and minor, as we discussed in our blog post on “What are Modes in Music?“

Order of Sharps and Flats

Sharps and flats in key signatures are always presented in a specific order, which is crucial to remember when reading and interpreting key signatures.

For sharps, the order is F, C, G, D, A, E, B.

The mnemonic widely used to remember this sequence is “Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle.” However, another popular alternative is “Fat Cats Go Down Alleys Eating Birds.”

For flats, the order is the reverse: B, E, A, D, G, C, F.

A mnemonic that corresponds to this sequence is “Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles’ Father,” which is essentially the phrase “Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle” reversed. Alternatively, a popular mnemonic phrase is “Before Eating A Doughnut Get Coffee First.”

These order rules apply regardless of the key. For instance, if you’re in the key of D major (two sharps), those sharps will always be F# and C#. For the key of B flat major (two flats), those flats will be Bb and Eb.

Understanding the order of sharps and flats is essential in correctly interpreting key signatures, contributing to more accurate and efficient music reading. For a more detailed explanation, please refer to our article on the Circle of Fifths.

Shortcuts for Identifying Key Names from Key Signatures

In the realm of key signatures, a few practical shortcuts can help you quickly identify the key name.

- Sharps: If the key signature contains only sharps, add a half step to the last sharp in the key signature to determine the key. For instance, if the last sharp is F#, adding a half step would give you G. Therefore, the key is G Major or its relative minor, E minor. Similarly, if the last sharp is C#, adding a half step gives you D. Therefore, the key is D Major or its relative minor, B minor.

- Flats: When the key signature contains two or more flats, the key is the second-to-last flat. For example, if the key signature contains Bb, Eb, Ab, and Db, the second-to-last flat is Ab. Hence, the key is Ab Major or its relative minor, F minor.

- The F Major Exception: A special case exists for the key signature with just one flat (Bb). As there is no second-to-last flat in this situation, it’s important to memorize that the key for this signature is F Major or its relative minor, D minor.

- No Sharps or Flats: Lastly, when the key signature has no sharps or flats, the key is C Major or its relative minor, A minor. No other rules apply to this case, making it a straightforward recall task.

By mastering these shortcuts, you’ll be able to swiftly and accurately identify key names from their signatures, saving you valuable time during composition or analysis.

Key Signatures and Modulation

As we navigate the realm of music theory, we encounter concepts that change how music is composed and experienced. One of these vital concepts is “modulation.”

Simply put modulation changes from one key to another within a piece of music. This shift in key signature, even if temporary, allows for a wide range of expressive possibilities and is an essential tool for songwriters and composers.

Understanding modulation begins with a solid grasp of key signatures. As we have explored in previous sections, the key signature sets the tonal landscape for a piece of music. When the music modulates, this landscape changes – the hills and valleys of our musical map shift, leading us into new sonic territories.

Modulation can be subtle, gently guiding the listener into a new key. Other times, it can be abrupt and dramatic, creating a jolt of energy. Regardless of how it’s done, modulation adds interest, variety, and depth to music, preventing monotony and predictability.

In music, there are various ways to modulate or change key. However, for the scope of this article, we’ll consider one of the most common types – modulation to the dominant key, also known as moving up a perfect fifth. If we’re in the key of C Major, the dominant key is G Major.

To illustrate this, let’s imagine a simple piece of music that begins in the key of C Major. We would see no sharps or flats in the key signature, and our melody might revolve around the notes of the C Major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B).

Let’s introduce some variety and excitement by modulating to the dominant key. Since the dominant of C Major is G Major, we will aim to shift our melody to revolve around the notes of the G Major scale (G, A, B, C, D, E, F#).

You would clearly notice this change in the music as it might feel like a lift or a shift to a brighter sound. The key signature would also change, showing one sharp (F#), which signifies the new key of G Major.

Then, after spending some time in this new key, we might return to our original key of C Major, creating a sense of homecoming or resolution.

This modulation type often appears in a piece’s middle section (or bridge) to contrast before the music returns to the original key. Our previous article, “What is a Key in Music,” explored other examples and types of modulation.

Remember, modulation is an advanced topic, and understanding it fully requires a solid foundation in many areas of music theory, including scales, intervals, and keys. If you’re new to these topics, revisiting our previous articles might help to consolidate your understanding.

Conclusion

Navigating the world of music theory is like learning a new language. Still, as we’ve discovered in this article, the more you familiarize yourself with the basic building blocks, the more you’ll see patterns and connections. Understanding key signatures is an essential part of this journey.

Key signatures define the tonal center of a piece of music, setting the stage for the following melodies and harmonies. They simplify music notation by showing us at a glance which notes are sharp or flat throughout a piece, thereby reducing the clutter of accidentals on the staff.

We’ve learned that each major and minor key has its unique key signature, represented by a specific sequence of sharps or flats. These are arranged in a specific order, a detail that can simplify reading key signatures once you’ve committed it to memory.

We also delved into the concept of modulation, a shift in the key signature within a piece of music. This technique can add variety and emotional depth, creating contrast and interest in the composition.

While this article has primarily focused on modern Western music theory principles, it’s worth mentioning that the tonal system we are discussing was largely standardized during the Western common-practice period.

This period spans from the mid-Baroque through the Classical and Romantic eras, roughly from 1650 to 1900, when common-practice tonality emerged and evolved, significantly shaping the music of these times.

For those who would like to delve deeper into how the tonal system has shaped the music of the common-practice period and how it contrasts with other musical idioms, you might find the article on the Western common-practice period (ext. link) insightful.