A musical scale is a sequence of notes arranged in ascending or descending order of pitch. Scales are a foundational musical element, providing a framework for melody and harmony creation.

Introduction

This article delves into a fundamental concept in music: what is a musical scale. A scale in music is a set of musical notes arranged in an ascending or descending order, typically following a predetermined sequence of intervals.

Scales are involved regardless of the style or genre, whether it’s a classical symphony, a pop anthem, a jazz improvisation, or a hard-hitting rap verse. They help define the tonality of a piece (whether it sounds happy, sad, mysterious, and so forth) and provide a roadmap for the composition and arrangement of music.

Understanding musical scales is key to music theory, an essential aspect of composing and songwriting. It’s like knowing the rules of grammar before writing a novel. They can guide you in creating chord progressions, crafting memorable melodies, and even improvising a soulful solo.

Don’t be daunted by the technicality of it all. We will break it down, step by step, from the basic structure of a scale to various types of scales and their characteristics, the fascinating world of modes, and how scales tie into chord progressions and melodies.

Whether you’re an aspiring musician, a songwriter, a seasoned composer, a music producer, or a music enthusiast, a solid understanding of musical scales is an invaluable tool.

The Basic Structure of a Musical Scale

Let’s think of a musical scale as a roadmap that outlines the melody and harmony’s path. It’s time to examine this pivotal structure in greater depth.

Definition and Importance of Musical Scales

Simply put, a musical scale is an arranged collection of notes organized by ascending or descending pitch.

But why should we care about scales? Scales are the backbone of melody and harmony across virtually all forms of music. They offer a pool of notes we employ to form melodies and harmonies. Every scale owns a specific “flavor” or “color” that shapes the emotional tone of a piece.

For example, a major scale is typically linked with uplifting or joyous moods. In contrast, a minor scale tends to bring about sorrow or introspection.

The Components of a Musical Scale

Let’s delve into the primary elements of a musical scale.

- Tonic: The tonic is the starting note of the scale, often called the “home” note. This is the base note upon which all other notes in the scale are compared. The tonic note is a relaxation, closure, or resolution point in a musical context. It’s akin to home plate in baseball; we often start from and return to this note.

- Intervals: Intervals represent the gaps between each note in a scale. These are measured in whole and half steps (tones and semitones). Each scale has a unique interval sequence, resulting in distinct aural qualities. For instance, a major scale adheres to a pattern of whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half steps.

- Ascending and Descending Sequences: Scales can be articulated in ascending order (moving from lower to higher pitch) or descending order (moving from higher to lower pitch). Certain scales, such as the melodic minor, alter the interval order depending on whether you’re ascending or descending.

- Octave: An octave is the gap between a note and another with twice its frequency. Simply put, it’s the same note but at a higher or lower pitch. Most scales span across an octave and start afresh after reaching the octave of the tonic.

Getting to Know the Scale Degrees

In music, the term “scale degrees” is used to designate the specific position of each note within a scale. We begin counting from the initial note of the scale, labeling it as one. Following that, the succeeding note becomes two, and this numbering continues sequentially, ascending throughout the scale.

Each degree also uses a specific term, especially in more formal musical discussions. Here’s a brief overview:

| Degree | Formal Term | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | Tonic | The root or starting note of the scale. It’s the home base to which all other notes are related |

| 2nd | Supertonic | Directly above the tonic, often serves as a passing note between the tonic and mediant |

| 3rd | Mediant | Midway between the tonic and the dominant. This degree often determines the scale’s major or minor quality |

| 4th | Subdominant | Just below the dominant, it’s often used as a way station between the tonic and the dominant |

| 5th | Dominant | The fifth note in the scale, it’s the second most important note after the tonic. It often creates tension that is resolved by returning to the tonic |

| 6th | Submediant | Midway between the tonic and the leading note. It often has a contrasting character to the tonic in a scale |

| 7th | Leading Note | Immediately below the tonic, it creates a strong pull towards the tonic, especially in major scales |

| 8ve | Tonic | An octave higher than the root, it returns to the tonic, reinforcing the sense of home and closure |

Although formal terminology adds a touch of sophistication, using numerical degrees (second, third, etc.) is usually adequate for casual musical discussions. However, it’s worth noting that “Tonic” and “Dominant,” representing the first and fifth degrees, are frequently used in everyday music conversations.

Let’s cover a few more handy terms. When two distinct instruments or voices play the same pitch, we call it “unison.” If you play the same note, but it’s eight scale degrees higher, we refer to it as an “octave,” a term coming from the Latin word “octo,” meaning “eight.”

Understanding scale degrees is valuable when you’re explaining the intervals between notes. You can refer to these scale degrees rather than counting in half-steps or whole-steps.

For instance, take the notes C and D. If we consider C as the first degree, D becomes the second degree. Hence, the interval between them is known as a “second.” If you’re looking at the interval between C and E, as they’re the first and third degrees, we call it a “third.” Similarly, the interval between C and F, the first and fourth degrees, is a “fourth.” The pattern goes on like this through the scale.

The Tonic of a Musical Scale

Referred to as the “home note,” the tonic is the initial note in a scale. It’s a cornerstone in setting the tone for a musical piece, often the starting and concluding point.

This concept of “home” is responsible for the satisfying sense of resolution we feel when melodies return to the tonic.

Generally, pinning down the tonic is a simple task. It’s the introductory note of a scale. For instance, on a D Major scale, D is the tonic. For an A minor scale, A holds that position. Remember that whether the scale is ascending or descending, the tonic remains constant.

In melodic lines, the tonic frequently serves as the opening and closing note, giving melodies a place to start and end.

Likewise, in harmony, the tonic chord (formed on the tonic note) offers a resolution or point of stability in chord progressions. This home note impacts the overall composition and guides the relationships between other notes.

Understanding Intervals

In musical terminology, an interval is the pitch distance separating two notes. Intervals are the fabric of scales and the foundation of melodies and harmonies. Comprehending intervals allows us to decode and group sounds, empowering us to create and replicate music effectively.

Intervals come in two main forms: melodic and harmonic.

- Melodic Intervals occur when notes are played one after the other, forming the backbone of most melodies.

- Harmonic Intervals occur when two notes are played simultaneously, resulting in harmony. Chords are harmonic intervals.

Intervals have qualities that describe their acoustic characteristics:

- Perfect Intervals: Unisons, 4ths, 5ths, and octaves fall into this category. Their label “perfect” comes from the harmonious balance they offer.

- Major and Minor Intervals: Major intervals are found in the major scale. If you reduce a major interval by a half step, it becomes a minor interval.

- Augmented and Diminished Intervals: An augmented interval is a half-step larger than a perfect or major interval. A diminished interval is a half-step smaller than a perfect or minor interval.

Recognizing intervals within scales is vital to understanding and constructing music. Let’s consider a G Major scale. From G to A is a whole step (major 2nd), G to B is a major 3rd, G to C is a perfect 4th, and so forth.

Intervals are the fundamental constituents of melodies and harmonies. In a melody, the interval relationships shape patterns and contours that our ears interpret as tunes.

For harmony, intervals form chords that provide a foundation for these melodies. The selection of intervals utilized in a musical piece substantially influences its emotional impact, genre, and expressive power.

For a more comprehensive understanding of the topic, refer to this post about intervals.

Introduction to Musical Scales

A scale is a fundamental tool in music creation, serving as a framework for melodies, harmonies, and chord progressions. Musical scales consist of notes ordered in ascending or descending pitch sequences.

The arrangement of these scales hinges on specific sequences of whole and half steps, along with the total count of notes they encompass. Each scale presents its distinct character.

Diatonic Scales

Diatonic scales consist of seven notes with a specific pattern of whole and half steps.

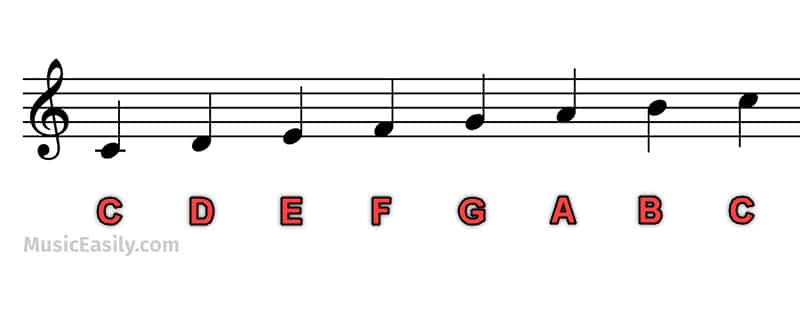

Major Scale

The major scale, often called “the scale” due to its prevalence, follows a specific pattern: Whole-Whole-Half-Whole-Whole-Whole-Half (W-W-h-W-W-W-h). For example, the C Major scale would be: C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C.

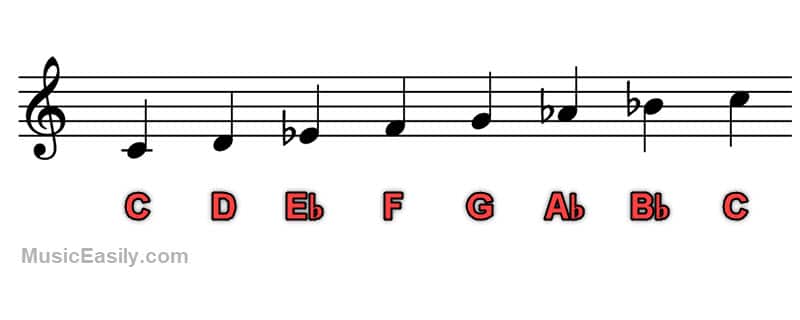

Minor Scale

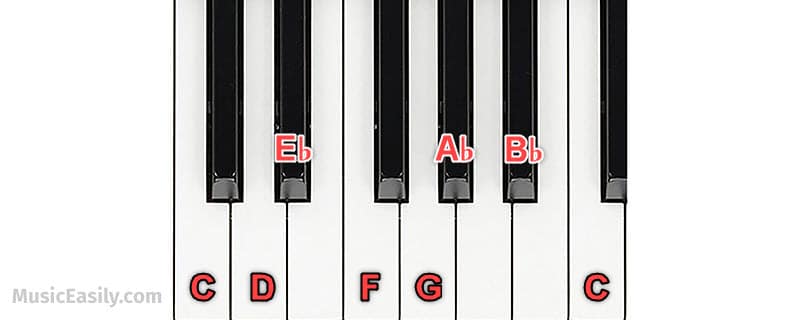

The natural minor scale has a different pattern of intervals: Whole-Half-Whole-Whole-Half-Whole-Whole (W-h-W-W-h-W-W). An example of a minor scale would be the C Minor scale: C-D-Eb-F-G-Ab-Bb-C.

Understanding Relative Major and Minor Scales

A fascinating aspect of musical scales is their inherent interconnectedness, clearly exhibited in the relationship between major and minor scales. Each major scale has a corresponding relative minor scale, and vice versa. This bond is built on a shared key signature – the identical collection of sharps or flats – between a major scale and its relative minor.

How is this relationship established? Let’s delve into the details.

Determining the Relative Minor

If we start on the sixth degree of a major scale and continue past the octave, the step pattern aligns precisely with that of a minor scale. As a reminder, a major scale follows a pattern of Whole-Whole-Half-Whole-Whole-Whole-Half (W-W-h-W-W-W-h), while a minor scale adheres to Whole-Half-Whole-Whole-Half-Whole-Whole (W-h-W-W-h-W-W).

The sixth degree in a major scale becomes the tonic of its relative minor scale. This transition occurs because the Whole-Half-Whole pattern, characteristic of a minor scale, begins on the sixth degree of a major scale.

For example, consider the C Major scale: C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C. Counting up to the sixth degree, we find “A.” Consequently, the relative minor of C Major is A Minor.

Alternatively, you can also determine the relative minor of a major key by counting half steps or semitones. Start from the root note of the major key and count down three half-steps. The note you land on is the root of the relative minor key.

So, if you start on a C and count down three half steps, you’ll land on A, the root note of A minor.

Determining the Relative Major

Similarly, if we start on the third degree of a minor scale and continue past the octave, the sequence of steps aligns with that of a major scale.

The third degree in a minor scale becomes the tonic of its relative major scale. This transition occurs because the Whole-Whole-Half pattern, characteristic of a major scale, begins on the third degree of a minor scale.

For instance, in the A Minor scale (A-B-C-D-E-F-G-A), the third degree is “C.” Thus, the relative major of A Minor is C Major.

You can also find the relative major of a minor key by counting semitones or half-steps. Start from the root note of the minor key and count up three half-steps. The note you land on is the root of the relative major key.

For example, if you start on an A and count up three half steps, you’ll land on C, which is the root note of C Major.

The beauty of the major-minor pairing lies in its reciprocity. Whether you start with a major or minor scale, you can identify its relative counterpart. This two-way relationship underscores the deep connection between major and minor scales.

The table below showcases relative major and minor pairs to visualize this relationship better.

| Major Scale | Relative Minor Scale |

|---|---|

| Cb Major | Ab Minor |

| C Major | A Minor |

| C# Major | A# Minor |

| Db Major | Bb Minor |

| D Major | B Minor |

| Eb Major | C Minor |

| E Major | C# Minor |

| F Major | D Minor |

| F# Major | D# Minor |

| Gb Major | Eb Minor |

| G Major | E Minor |

| Ab Major | F Minor |

| A Major | F# Minor |

| Bb Major | G Minor |

| B Major | G# Minor |

It may be helpful to check the Circle of Fifths article to understand how different major and minor scales are related.

Pentatonic Scales

Pentatonic scales consist of five notes, which is why they’re named after the Greek word “penta,” meaning “five.” These scales are prevalent in various music genres around the globe due to their simplicity and versatility.

Major Pentatonic Scale

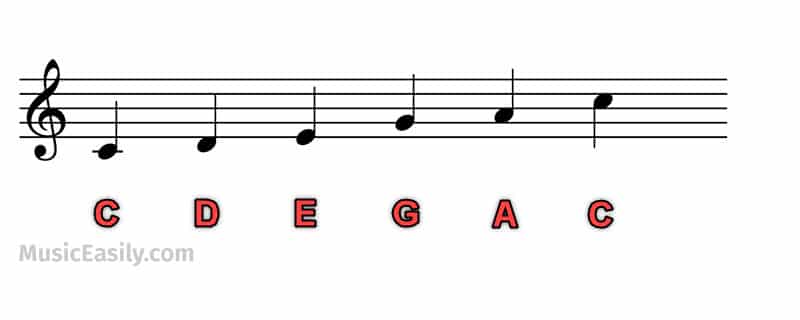

The major pentatonic scale is a five-note scale that eliminates the fourth and seventh notes from the major scale. This results in a happy, uncomplicated sound. The C Major Pentatonic, for example, consists of the notes C-D-E-G-A-C.

Minor Pentatonic Scale

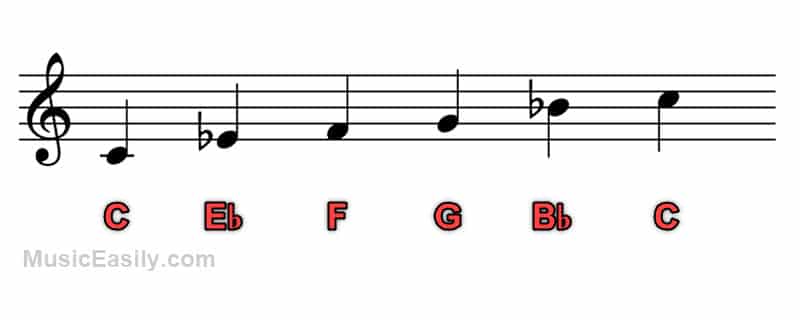

The minor pentatonic scale, on the other hand, has a darker and more somber mood. It’s created by omitting the second and sixth notes from the natural minor scale. An example of a minor pentatonic scale is the C Minor Pentatonic: C-Eb-F-G-Bb-C.

Blues Scale

The term “blues scale” refers to several scales, each with unique characteristics. However, the most commonly discussed version is a hexatonic or six-note scale. This is a minor pentatonic scale with an added flat 5th, often called the “blue note.” This “blue note” gives the blues scale its distinct “bluesy” sound, contributing tension, color, and a touch of dissonance.

We often focus on this particular version of the blues scale due to its widespread use in various forms of music, from blues and rock to jazz and even pop. With its added “blue note,” this scale provides musicians with a potent tool for expression and improvisation.

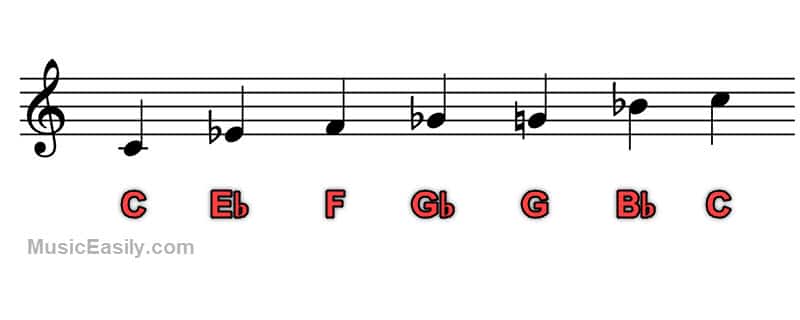

For example, consider the C Blues Scale: C – Eb – F – Gb – G – Bb – C. Note that Gb is this scale’s “blue note.”

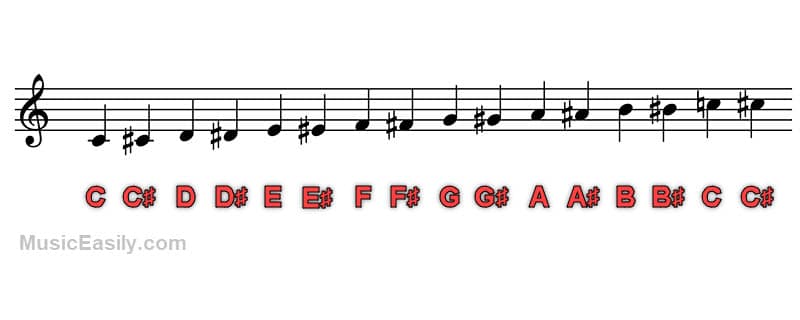

Chromatic Scale

The chromatic scale contains all twelve pitches of the octave, arranged in ascending or descending half-steps. This scale is typically used for color and tension in various music styles. For example, the C Chromatic Scale is: C-C#-D-D#-E-F-F#-G-G#-A-A#-B-C.

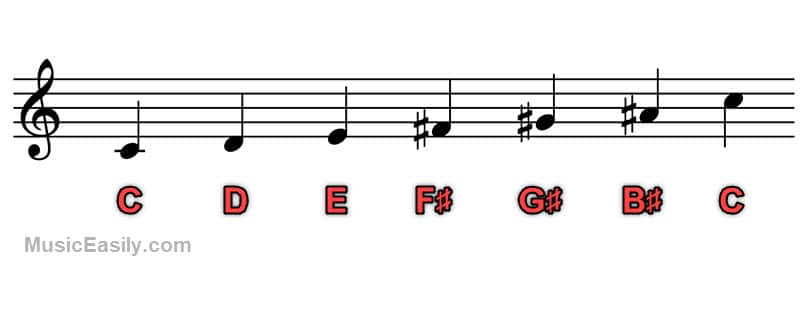

Whole Tone Scale

Finally, the whole tone scale consists of six notes with the same interval (whole step) between each note. This scale creates an ambiguous, dream-like mood and is often used in Impressionist music. An example of a whole tone scale would be: C-D-E-F#-G#-Bb-C.

Other Types of Scale Classification

Although our focus in this article is on diatonic, pentatonic, blues, chromatic, and whole tone scales, musical scales can be classified based on the number of distinct pitch classes they encompass, such as the octatonic scale (8 notes per octave), used in jazz and modern classical music, as you can find in this Wikipedia article (ext. link).

A Brief Introduction to Modes in Music

A notable extension of our understanding of musical scales is the concept of “modes.” In the simplest terms, modes in music are unique variations of a diatonic scale created by starting the sequence from a different degree, each offering a distinct tonal character and emotional resonance.

If you’d like to explore modes and their role in music, we invite you to read our comprehensive article about Modes.

Learning and Practicing Musical Scales

Navigating the terrain of musical scales can initially feel quite daunting. However, with the correct strategies and resources, you can master it. Let’s explore some handy tips and tricks for learning and perfecting scales. We will also explore some useful invaluable tools and resources, whether you’re an instrumentalist or a music producer crafting sonic magic on your digital audio workstation (DAW).

On An Instrument

- Beginning with Major and Minor Scales: A good starting point is with major and minor scales. They form the backbone of Western music and are pervasive across nearly all genres. Get to grips with their structures and sounds, and practice them in various keys.

- Metronome Utilization: Practicing alongside a metronome aids in building a solid sense of timing and rhythm. Start with a slower tempo and steadily increase it as your precision and comfort level improve.

- Consistent Practice: Regular and consistent practice is the secret sauce. Carve out a daily time slot dedicated exclusively to scales. This regularity will reinforce muscle memory and enhance your familiarity with scale patterns and tonalities.

- Scale Transposition: Once a musical scale in a particular key feels comfortable, try transposing it to other keys. This exercise will aid in gaining a comprehensive understanding of your instrument’s keyboard or fretboard.

In Music Production Software

- Use MIDI: MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) is an excellent resource for learning and practicing musical scales. Input a scale in a certain key and then easily transpose it to any other key you choose.

- Use Scale Plugins: Many DAWs offer plugins or integrated features that assist you in working within a particular musical scale. These tools are invaluable for learning, practicing, and composing within scales.

- Recreate Songs: Try reproducing simple melodies or chord progressions from songs on your DAW. This practice will allow you to understand how scales are employed in real-world musical contexts.

Conclusion

Getting to grips with musical scales is a crucial part of making music. Scales are the bedrock of harmonies, melodies, and chords, shaping a piece of music’s emotional tenor and feel.

Whether you’re a musician perfecting your performance, a songwriter crafting new tunes, a sound designer shaping audio, or a music fan looking for deeper understanding, mastering musical scales is a surefire way to enhance your musical abilities. Think of it as becoming more fluent in the language of music.

It’s essential to remember that learning scales in music goes beyond rote learning of note sequences—it’s about comprehending how these notes relate to each other, how they interact, and the distinct “character” they bring to the overall musical piece. This knowledge is a guidepost, directing your creative decisions and adding depth to your musical journeys.