Whole steps and half steps in music, also known as tones and semitones, are the smallest intervals between different pitches in Western music. They are essential for constructing melodies, chords, and scales on musical instruments, such as the piano and guitar, and play a pivotal role in shaping the emotional contour of a musical piece.

Introduction to Whole Steps and Half Steps

As you delve into the intriguing world of music theory, you’ll first encounter two essential concepts – the half step and the whole step. Even though these concepts are relatively straightforward, they are, in fact, the core elements of music, playing a crucial role in crafting melodies, chords, and scales.

Western music recognizes the smallest pitch interval as a half step, or semitone. You can easily see this on a piano by moving from any key to its nearest neighboring key, regardless of whether it’s black or white. If you’re more familiar with a guitar, a half step is the distance from one fret directly to the next.

Conversely, a whole step, also known as a whole tone or simply a tone, is equivalent to two half steps. This involves skipping over the nearest key on a piano keyboard and proceeding to the next one. On a guitar, a whole step encompasses the distance between two frets that have one fret in between them.

Whole and half steps are much like the genetic code of music – they form the basis of scales and chords, contributing to the creation of tunes and compositions. They profoundly impact the mood of the music, stirring tension and resolution and molding the emotional journey that music narrates. Grasping these steps is much like learning the alphabet before diving into reading and writing.

The application of whole steps and half steps isn’t a recent phenomenon. This system has a profound historical origin and forms the foundation of the tonal music tradition, tracing back to the Baroque period (1600-1750). During this epoch, the major and minor scales, constructed based on specific sequences of whole and half steps, came to underpin Western music.

The approach of building scales and subsequently developing chords opened up a myriad of harmonic possibilities, leading to the rich and diverse music we relish today.

Whole steps and half steps signify more than just musical increments. They are the language through which musicians express thoughts and emotions.

Understanding Accidentals

Music is often compared to a universal language, transcending cultural and linguistic barriers. But, like any other language, it has its unique syntax, symbols, and grammar. One such critical set of symbols in musical notation is “accidentals.” Accidentals are symbols that adjust the pitch of a note, either incrementing or decrementing it by a certain amount.

The significance of accidentals in music cannot be overstated. They enable the expression of a wide range of pitches beyond the seven basic notes of a standard scale (A, B, C, D, E, F, G). Accidentals allow musicians to articulate a more comprehensive array of emotions and subtleties by introducing diversity and intricacy to a piece of music.

We primarily deal with five types of accidentals: sharps, flats, naturals, double sharps, and double flats.

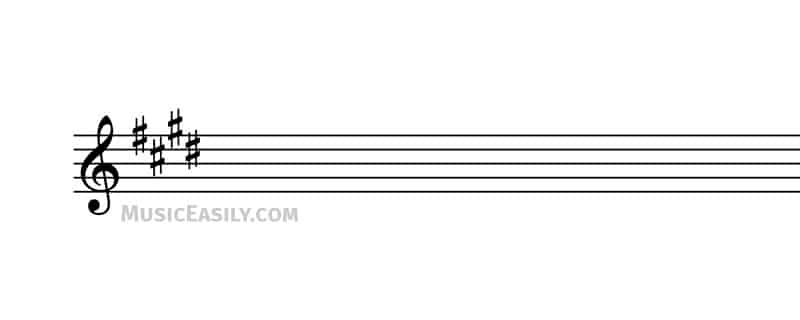

A sharp (symbolized by ‘#‘) elevates the pitch of a note by a half step, whereas a flat (marked by ‘b‘) diminishes the note’s pitch by the same amount.

Should we need to cancel the effect of a sharp or flat, a natural comes into play. A natural (represented by ‘♮‘) neutralizes a sharp or flat, restoring the note to its original, unaltered pitch.

For more dramatic pitch alterations, we have double sharps and double flats at our disposal. As you might guess, a double sharp (signified by ‘x‘) lifts the pitch of a note by two half steps or a whole step, and a double flat (indicated by ‘♭♭‘) lowers it equivalently.

The correlation between accidentals and whole steps/half steps is relatively straightforward. Whole and half steps are the fundamental increments of pitch variation, and accidentals are the mechanisms we utilize to implement these modifications.

Let’s delve into the placement of these accidentals on a music staff. You’ll frequently see sharps or flats immediately after the clef at the beginning of a line or space.

This is known as a “key signature” and applies to all notes of the same letter throughout the piece or until a new key signature is indicated. This key signature sets the tonality for the entire piece or section, providing a roadmap for the consistent pitch shift for certain notes, thereby reducing the need to mark each instance.

However, all types of accidentals, including naturals, double sharps, and double flats, can appear directly before the note they modify. These are typically used for temporary alterations that deviate from the key signature. For example, a note with a sharp sign (#) before it indicates that it should be performed a half step higher than its usual pitch.

Similarly, a note with a double sharp (x) raises the pitch by a whole step, and a natural (♮) cancels any previous accidentals and returns the note to its original pitch, so whether it’s in the key signature or before a note, accidental plays a crucial role in defining the pitch landscape of a piece of music.

We recommend checking out our comprehensive article about accidentals for a more in-depth exploration of this topic and its significant role in music.

The Concept of Enharmonic Equivalents

In connection to accidentals, the principle of enharmonic equivalents is noteworthy.

These are notes that have the same pitch but are represented differently. For instance, an F sharp (F#) is enharmonically equivalent to a G flat (Gb), denoting the same pitch but notated distinctively. Grasping this principle is crucial for accurate and flexible music reading and writing.

The application of accidentals and the understanding of whole and half steps equips musicians with a broader spectrum of notes, facilitating the rich diversity of music that resonates with us.

Whole Steps and Half Steps in Scales

Before we delve into the influence of whole and half steps in scales, we must comprehend what musical scales represent.

At its most basic, a scale is a sequence of notes ordered by pitch, either ascending or descending. Scales form the backbone of music, setting the tonality for a composition and serving as a guide for melodic and harmonic progression.

Various scales, like major and minor, are created using distinct sequences of whole steps and half steps. These sequences give each scale its unique sound.

Consider the major scale, a prevalent scale in Western music. The construction of the major scale follows a specific sequence of whole steps and half steps: Whole, Whole, Half, Whole, Whole, Whole, Half.

For instance, if we take C as our starting point, a C major scale would comprise the notes: C (whole step to), D (whole step to), E (half step to), F (whole step to), G (whole step to) A (whole step to) B (half step to) C.

Conversely, the natural minor scale, often associated with a moodier or more introspective sound compared to the major scale, follows a different sequence: Whole, Half, Whole, Whole, Half, Whole, Whole.

Thus, an A minor scale would include the notes: A (whole step to), B (half step to), C (whole step to), D (whole step to), E (half step to), F (whole step to), G (whole step to) A.

The specific sequence of whole and half steps shapes the character of a scale. By altering this sequence, we can derive different modes, each with a unique tonal color.

Modes are variations of musical scales that share the same notes as the major scale but begin and end on a different note within that scale. This change in the starting point creates a new pattern of whole and half steps, which makes each mode sound unique.

By altering the arrangement of whole and half steps in a scale, modes can evoke different emotions and moods in the music, even though they use the same group of notes as the original major scale.

To gain a deeper understanding of this topic, you may want to explore our comprehensive articles about musical scales and musical modes. Each article delves into its respective topic, providing further insight into the intricacies of music theory.

Whole Steps and Half Steps on Piano

To truly grasp the essence of whole and half steps in music, one must see them in action. This section will explore how these steps manifest on the piano, an instrument that beautifully illustrates these musical distances.

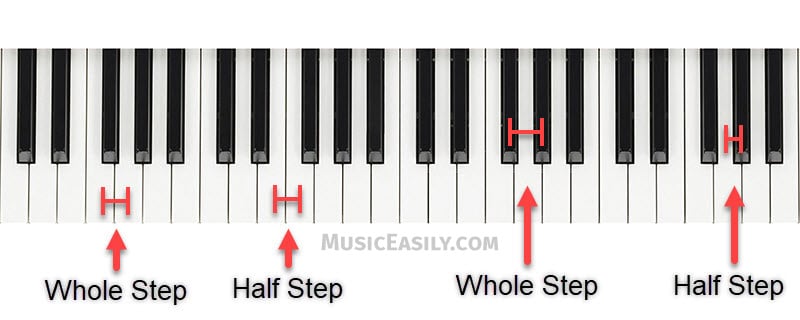

First, let’s familiarize ourselves with the layout of a piano keyboard. Typically, a piano keyboard showcases a recurring pattern of 12 keys: seven are white, and five are black. The white keys correspond to the natural notes (A, B, C, D, E, F, G), which are derived from the musical alphabet, and the black keys are the accidentals (sharps and flats).

Identifying whole steps and half steps on a piano is relatively straightforward. A half step, or semitone, is the smallest possible interval between two notes. On a piano, this is represented by the distance from one key to its immediate neighbor, whether black or white. For example, progressing from a C to a C# signifies a half step, as does advancing from an E to an F, despite lacking a black key.

Conversely, a whole step, or whole tone, is equivalent to two half steps. In piano terms, this means bypassing one key and landing on the subsequent one. For instance, a journey from a C to a D constitutes a whole step, as does a leap from an E to an F#, bypassing the F.

It’s advisable to cement this understanding with some hands-on exercises. Start by playing a sequence of half steps, gradually ascending and descending the keyboard. Once you’re comfortable with this, shift your focus to whole steps.

The black and white keys on a piano play a significant role in visually distinguishing whole steps and half steps. The black keys, representing the sharps and flats, fill the intervals between certain white keys, helping us differentiate between whole steps and half steps.

For example, a progression from C (a white key) to C# (a black key) is a half step, but a leap from C to D (omitting the black key in the middle) is a whole step.

Comprehending whole and half steps on the piano is vital to mastering scales, chords and, eventually, performing entire pieces. Even if your primary interest lies in guitar or other instruments, this knowledge is transferable and equally essential.

Understanding these concepts provides a foundational understanding of how music is structured, which is crucial regardless of the instrument you choose to express your musical creativity.

Whole Steps and Half Steps on Guitar

While the piano may offer a more visual representation of whole and half steps, the guitar is another instrument where these musical increments play a significant role. Let’s explore how to identify these steps on the guitar’s fretboard.

A guitar’s fretboard may appear daunting at first, but fear not! We’ll demystify it step by step. A typical guitar has six strings, each with a unique base pitch when strummed without pressing down on any fret. From the thickest to the thinnest, these open strings sound the pitches E, A, D, G, B, E. The frets, the metal strips that cross the fingerboard, allow us to change these base pitches.

Now, let’s bring the concept of whole steps and half steps into the realm of the guitar. On a guitar, a half step equates to the distance between one fret and its direct neighbor. For example, if you strike the open D string (the third thickest) and then press down at the first fret, you’ve ascended by a half step, arriving at a D# or Eb.

A whole step on a guitar translates to a gap of two frets. So, if you start on an open D string and press down on the second fret, you’ve made a whole step jump, landing on an E.

To reinforce this understanding, practice some hands-on exercises. Begin with playing half steps on one string, moving progressively along the fretboard one fret at a time. Once comfortable, progress to practicing whole steps.

The fretboard’s layout, combined with the open strings, forms the foundation for understanding whole steps and half steps on the guitar. The open strings offer the root notes, and each fret provides a way to increment the pitch by half steps.

Application in Guitar Tuning and Understanding the Fretboard

Tuning is fundamental to playing the guitar, ensuring the instrument sounds its best. Comprehending whole steps and half steps can significantly ease the process of tuning your guitar.

Tuning your guitar involves adjusting the string tension until each sounds at the desired pitch. A guitar fretboard is a complex network of notes, with each fret corresponding to a half step up or down in pitch.

The standard tuning for a guitar, from the thickest to the thinnest string, is E, A, D, G, B, E. Note that each string is a perfect fourth (or five half steps) away from the next, except the B string, which is a major third (or four half steps) away from the G string.

For tuning your guitar, the fifth-fret method is a commonly used technique. This method involves pressing down on the fifth fret of a string and matching the pitch of the next higher string. However, when tuning the second string (B), you should press down on the fourth fret of the G string.

Alternate tunings provide a real-world application of whole and half steps in guitar tuning. These involve adjusting specific strings up or down by a whole step or half step. For instance, in Drop D tuning, the lowest (sixth) string is tuned down by a whole step from E to D. This changes the tonal qualities and available chord voicings on the guitar, opening up new musical possibilities.

For those interested in diving deeper into the intricacies of musical tuning, we recommend exploring the concept of tuning systems, which define the exact pitches represented by whole and half steps. This topic goes beyond the scope of this article, but you can expand your understanding by checking out this page on Musical Tuning (ext. link).

Whole Steps and Half Steps in Chords

Chords provide the harmonic backbone of music, delivering emotional depth and complexity. But what are chords, and how do whole and half steps come into play in their formation? Let’s delve into these questions.

In its simplest form, a chord combines three or more distinct pitches sounding simultaneously. The basic types of chords you’ll encounter in music include major, minor, augmented, and diminished chords. Each chord type possesses a unique sonic character, largely determined by the arrangement of whole and half steps within their structure.

If you’re keen on going deeper into chords, check out our comprehensive article, which offers a more in-depth exploration of chords.

A major chord, for instance, is constructed using a specific pattern of whole and half steps. Starting from the root note (the note that names the chord), a major chord is built using a pattern of four half steps (or two whole steps) to the next note, followed by three half steps to the third note. This pattern of steps (whole, whole, and then half, whole) creates the sound of a major chord, often described as happy or bright.

Conversely, a minor chord, typically sounding unhappy, uses a slightly different pattern. From the root note, you ascend by three half steps to the next note and then by four half steps (or two whole steps) to the third note. This pattern of steps (whole, half, and then whole, whole) gives the minor chord its characteristic sound.

Augmented and diminished chords also rely on specific patterns of whole and half steps. An augmented chord, which sounds tense and unresolved, is constructed by stacking two major thirds or two sequences of four half steps. A diminished chord, which typically conveys a sense of tension and instability, is built by stacking two minor thirds, or two sequences of three half steps.

Try building these chords on a piano keyboard to solidify these concepts. For instance, you could start with a C major chord.

On a piano, you’d start on a C, skip one white key (or move up by a whole step) to reach D, and then skip another white key (or move up by another whole step) to reach E. From E, you would skip one white key (or move up by a half step) to reach F and then skip another white key (or move up by a whole step) to reach G.

Understanding the role of whole and half steps in chord construction is fundamental to music theory. It allows you to understand how chords are built and provides a basis for exploring more complex harmonic concepts such as chord inversions, extensions, and progressions.

Conclusion

In this article we’ve discovered the critical roles of whole and half steps, accidentals, and their applications in scales, chords, and instrument playing.

These foundational units shape our understanding of music, whether we’re fine-tuning a guitar or composing a melody. As you continue your musical journey, keep these concepts in mind. They’re the keys to unlocking the vast language of music.