The Music Staff is a visual system of lines and spaces where musical notes are placed, serving as a blueprint for interpreting and performing music.

- Introduction

- The Basics of the Music Staff

- Understanding Clefs and Their Role in the Music Staff

- Mapping Pitch on the Music Staff

- Ledger Lines: Extending the Staff

- Stem Direction and Beaming

- Types of Music Staff

- Key Signatures and the Music Staff

- Time Signatures and the Music Staff

- Music Staff in DAWs and Notation Software

- Conclusion

Introduction

The music staff is the backbone for translating the sounds you hear into a form that can be visually understood, learned, and performed. The music staff is an elegant system of lines and spaces upon which musical notes are placed.

In this article, we’ll delve into the essentials of the music staff, exploring its basic structure, types, the relevance of different clefs, and how it serves as a map to denote pitch.

We’ll also touch on how other elements, used in conjunction with the staff, help convey rhythm in written music.

The Basics of the Music Staff

The music staff, or stave, is a series of five parallel horizontal lines. Together, they form a framework for placing musical symbols, including notes and rests. But these lines and spaces aren’t merely placeholders; they represent different musical pitches.

Essentially, the music staff is a graph that plots the highness or lowness of a note—the pitch—against time. In the following section, we’ll explore this concept of pitch on the music staff in more detail.

This graph-like representation creates a standard visual language for musicians. Regardless of their instrument, musicians can understand the melodies, harmonies, and rhythms conveyed through the arrangement of symbols on the music staff.

The Music Staff and Pitch

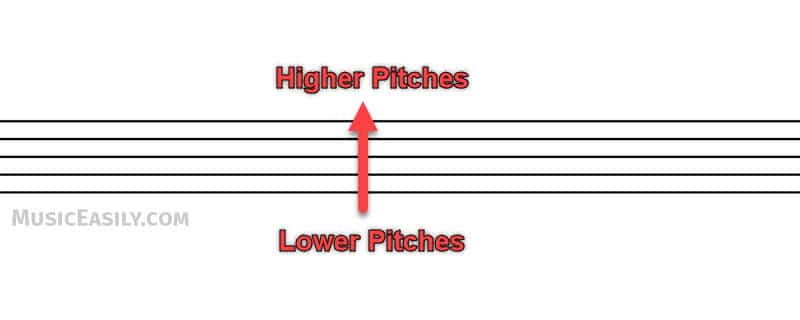

Understanding the concept of pitch in music is fundamental to interpreting the music staff effectively.

The music staff is an ingenious system for visually representing pitch. It’s akin to a vertical representation of pitches ranging from low to high. Each line and space on the staff corresponds to a specific musical pitch.

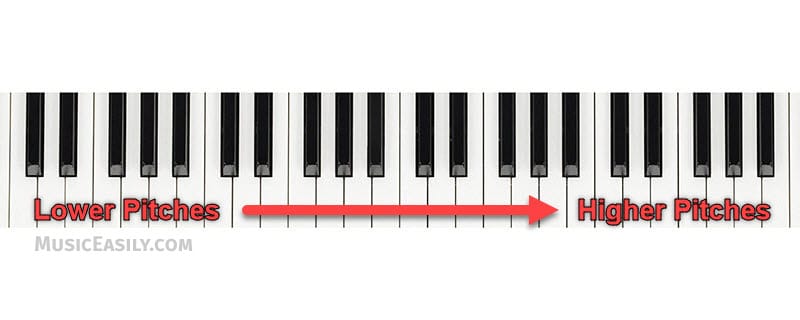

Now imagine the music pitches on a spectrum; the lowest notes would be on the left and the highest on the right. This is analogous to the layout of a piano keyboard.

The notes to the left on a piano keyboard are lower in pitch, while those to the right are higher. This means that you move from lower to higher pitches when you play notes from left to right. The black keys on the piano represent notes that have a pitch that falls in between the pitch of the adjacent white keys, adding more possibilities for creating melodies and harmonies.

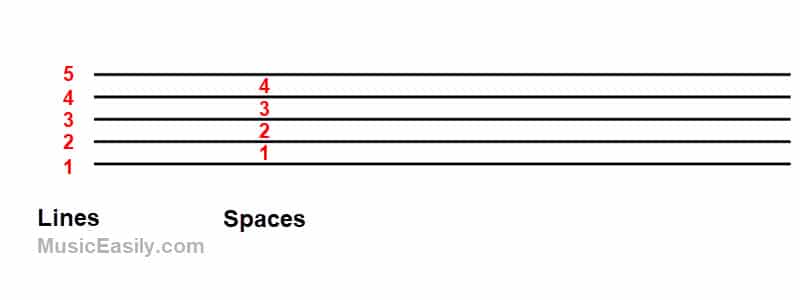

Counting Lines and Spaces

When reading a music staff, it’s important to know that lines and spaces are counted from the bottom upwards. So the bottommost line is the first line, the next line up is the second, and so on until the topmost line, which is the fifth.

Spaces are counted from the bottom upwards: the space between the first and second line is the first space, the space between the second and third line is the second space, and so on.

The Role of Lines and Spaces

Each line and space on the music staff corresponds to a unique position in the pitch spectrum. In the Western music system, pitches are named using the first seven letters of the alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. After G, the sequence repeats, starting from A again but at a higher pitch.

These lines and spaces don’t represent specific pitches on their own. Instead, a clef symbol, placed at the beginning of the staff, assigns them their specific pitch identities.

While the concept of clefs and their influence on pitch representation might seem complex, don’t worry. We will cover this fascinating topic in more detail in the next section. For now, remember that each line and space on the staff plays a crucial role in representing pitches in written music.

For a more in-depth exploration of how these letters correspond to specific pitches and how they cycle through the musical spectrum, consider delving into our detailed guide on the intricacies of musical notes.

Understanding Clefs and Their Role in the Music Staff

While the music staff serves as a visual representation of pitch, clefs are the map keys that precisely dictate where these pitches lie on the staff.

Clefs are an integral part of the music staff, establishing the foundation for how we understand, write, and interpret music.

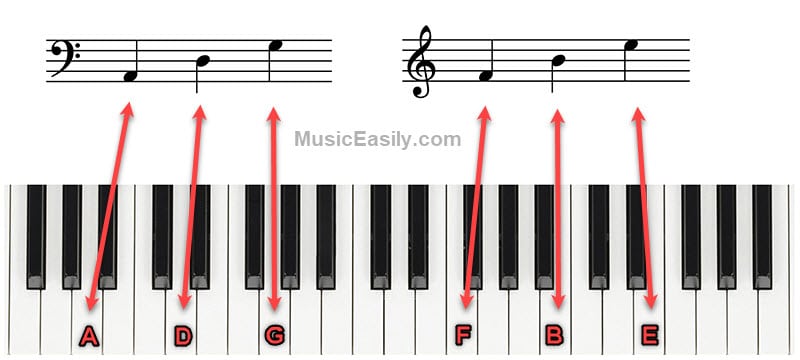

They are symbols placed at the leftmost part of a staff, providing a reference point that determines the pitches of the lines and spaces. In Western music, the most common clefs you’ll encounter are the treble and bass, but alto and tenor clefs also play key roles.

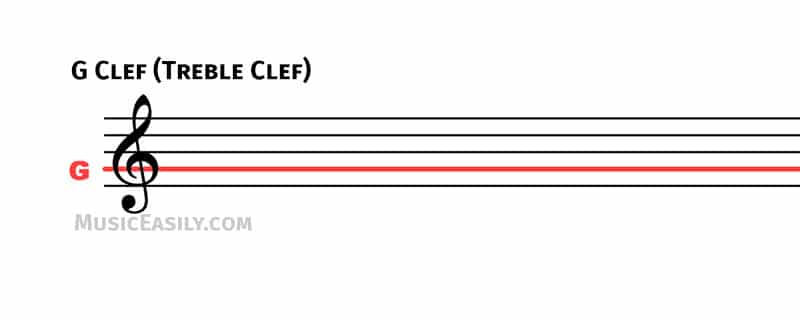

The Treble Clef

Also known as the “G clef” because it circles the line of the G note, the treble clef is widely used in music notation. It’s used primarily for higher-pitched instruments and voices.

This includes the right hand part of piano music, violin, flute, oboe, and female vocal parts, among others.

For those eager to delve deeper into the intricacies of the treble clef, our article about the treble clef is a must-read.

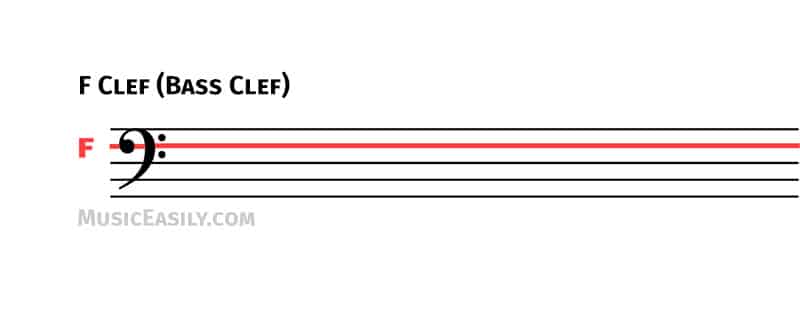

The Bass Clef

The bass clef, or the “F clef,” gets its name because the two dots surround the line representing the note F. It’s used to notate lower pitches for the left-hand part of piano music, cello, bassoon, trombone, male vocal parts, and more.

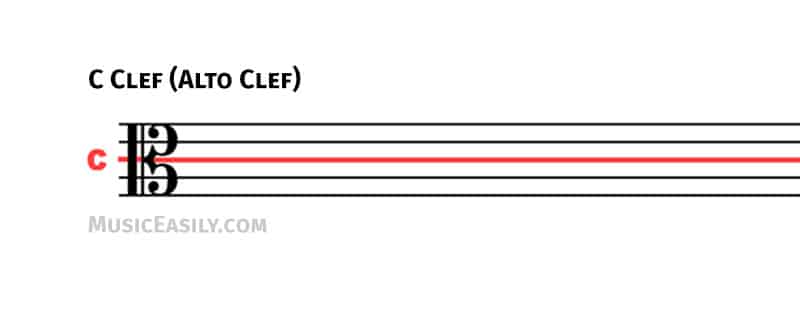

The Alto and Tenor Clefs

Although not as common as the treble and bass clefs, the alto and tenor clefs play essential roles in music, especially in orchestral music and choral arrangements.

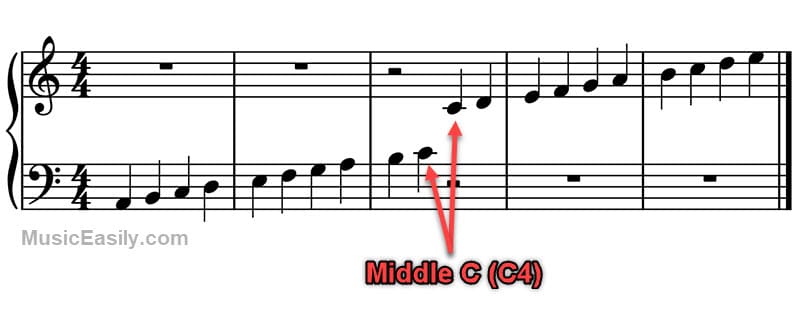

The alto clef, also known as the “C clef,” positions the middle C on the third line of the staff. This clef is most commonly associated with the viola and alto trombone.

On the other hand, the tenor clef, also a type of “C clef,” places the middle C on the fourth line. It’s often used for the upper ranges of the bassoon, cello, euphonium, double bass, and trombone.

Mapping Pitch on the Music Staff

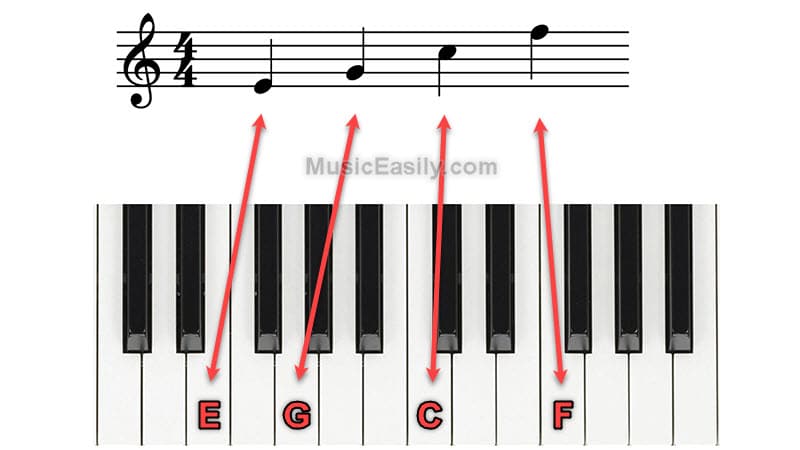

Now that we understand the role of clefs and their influence on pitch representation on the music staff, we can delve into the actual process of mapping notes.

When you map these notes onto the music staff, the correlation between their position and their pitch becomes clear. This allows us to translate music from a written form on the staff to played notes on a piano or any other musical instrument, effectively bridging the gap between visual notation and auditory experience.

When we place a note on a line or space, it indicates to the musician which note to play and how high or low it should be.

For example, on a staff with a treble clef, a note on the second line from the bottom tells the musician to play the note “G” at the specific pitch designated by that line. If the note is placed on the space just above that line, the musician will play “A,” one step higher in pitch.

Understanding that the staff does not inherently contain information about specific pitches is important. The lines and spaces could represent any pitch, depending on the clef used. The clef is what gives the staff its “coordinates” of pitch.

To truly appreciate how a staff represents pitch, consider a piano keyboard. A piano has white and black keys, the white keys representing the “natural” notes (A, B, C, D, E, F, and G), and the black keys representing the “sharp” or “flat” notes.

The sequence of lines and spaces on a staff maps directly onto this sequence of keys on the piano, making the staff a musical roadmap.

With this understanding, reading music becomes a matter of recognizing where on the staff a note is and translating that into a specific key on the piano—or a specific finger position on a guitar, valve position on a trumpet, and so on.

Regardless of the instrument, the staff provides a standardized, universal system for representing pitch.

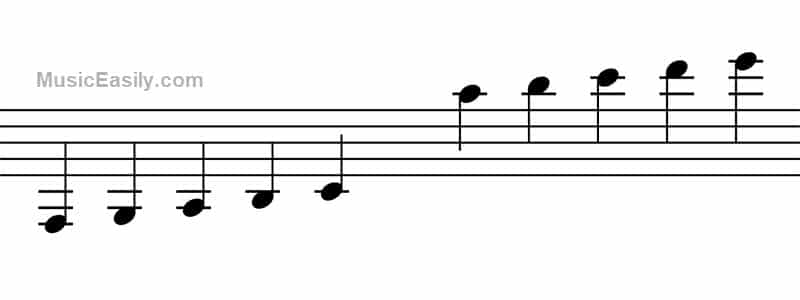

Ledger Lines: Extending the Staff

Music isn’t confined to the pitches represented within the staff’s five lines and four spaces. Notes can go much higher or lower, and that’s where ledger lines come in.

A ledger line, or leger line, is a short horizontal line added to extend the range of the staff when the notes to be notated are too high or too low to fit on it.

Ledger lines allow us to maintain a standardized five-line staff while accommodating the wide range of pitches that musical instruments can produce.

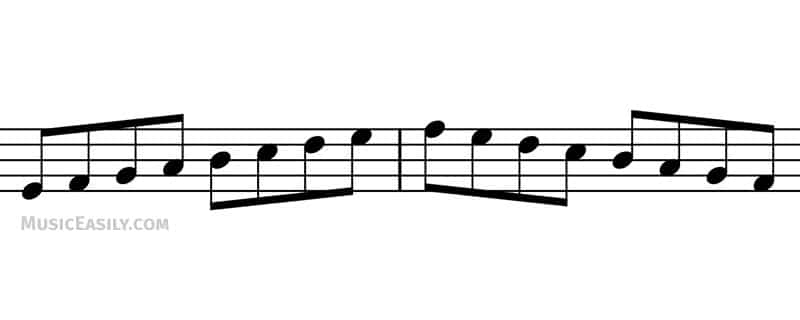

Stem Direction and Beaming

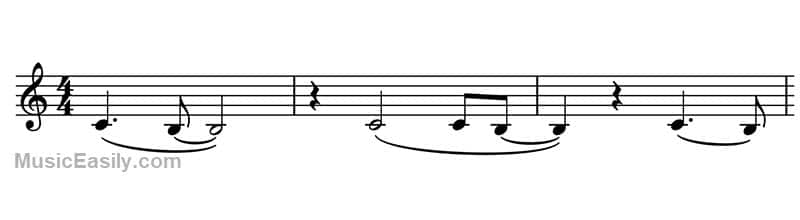

Stems on notes have rules regarding their direction. Half, quarter, eighth, and sixteenth notes, which have stems, should point either up or down depending on where the note is positioned on the staff.

If the note is positioned above or on the middle line, the stem should point down; if it is below the middle line, it should point up.

When two or more notes of shorter duration (like eighth or sixteenth notes) are beamed together, all the stems should point in the same direction as the first note in the group.

Though these are generally accepted practices in music notation, they are not strict rules. Depending on the musical context and aesthetic considerations, exceptions may occasionally occur.

Nevertheless, these guidelines greatly aid in maintaining a consistent and easily readable notation.

Types of Music Staff

In its vastness and diversity, music isn’t limited to just one kind of music staff. Indeed, various types of staff configurations suit different instruments, ensembles, and musical genres.

These variants typically fall into two categories: the grand staff and the single staff. Let’s explore each one and how they contribute to our understanding and performance of music.

The Grand Staff

The grand staff is what most people think of when they picture written music. It comprises two staves: one marked with a treble clef and the other with a bass clef.

The treble clef staff represents higher pitches, while the bass clef staff notates lower ones. The line connecting the two staves signifies the continuation of the pitch spectrum from one to the other.

The grand staff is most often used in piano music. Its design is ideally suited for the piano’s wide range of pitches and the ability of pianists to play multiple notes at once with both hands.

The right hand typically plays the notes on the treble clef staff, while the left hand plays the bass clef notes.

But the grand staff isn’t exclusive to the piano. Harp and marimba music often use the grand staff, as do some orchestral scores when notating multiple instruments or choirs together.

Single Staff

As the term suggests, a “single staff” refers to a standalone set of five parallel lines and four spaces in between them, used independently of any other staff system, such as the “grand staff.”

It’s widely used in music for single melodic lines, such as a solo voice, a single instrument part, or even the melody line in a song.

A single staff can be marked with a treble clef, bass clef, or any other clef depending on the range of the instrument or voice it is meant for. For instance, a violin part would typically be written on a single staff with a treble clef, while a cello part would use a bass clef.

In choral arrangements, single staff notation is typically employed for solo instruments or individual voice parts. Each line of music in this format is specifically tailored to one player or voice, enabling musicians to focus solely on their part.

This type of notation is common in pieces for wind, brass, string instruments, and solo vocals. Each instrument or voice has its separate staff line, making it easier for the musician to read and interpret their specific part.

The same pitch representation principles apply in the grand and single staff systems. The key difference lies in the range of pitches they can accommodate, determined by the type of clef used.

The choice between using a grand or single staff is often influenced by factors like the instrument being written for and the piece’s complexity.

By understanding these types of music staff, you can better navigate the diverse landscape of written music and gain greater insight into the structure and arrangement of musical works.

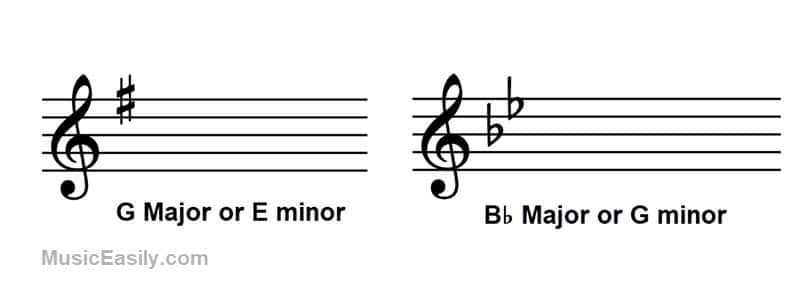

Key Signatures and the Music Staff

In music, the term “key” refers to the set of pitches that forms the basis of a music piece.

The key signature, situated immediately after the clef at the beginning of a line of musical notation, serves a pivotal role. It informs the reader of the piece’s key by indicating which notes will be played sharp or flat throughout the performance unless otherwise noted by additional accidentals.

Key signatures can have anywhere from zero to seven sharps or flats. For example, a key signature with no sharps or flats indicates the key of C Major/A minor. One sharp represents the key of G Major/E minor, while two flats suggests Bb Major/G minor, and so on.

The sequence of sharps and flats in key signatures follows a specific order — sharps: F, C, G, D, A, E, B; and flats: B, E, A, D, G, C, F.

Understanding key signatures not only streamlines reading and writing music but also guides composers and performers in conveying a piece’s intended mood and tonality.

By providing this context, key signatures allow musicians to focus less on individual notes and more on the expressive and harmonic aspects of the music.

If you’re intrigued by the idea of key signatures, our dedicated article on key signatures offers a deeper exploration of this topic.

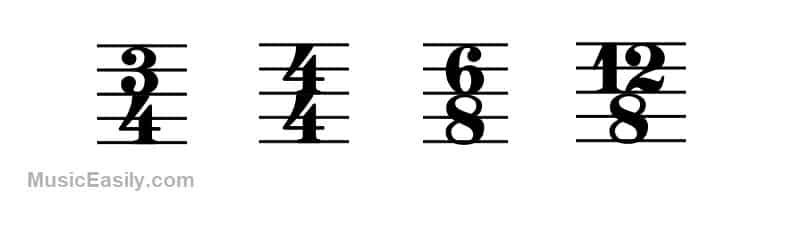

Time Signatures and the Music Staff

In music notation, time signatures are key to understanding rhythm, pacing, and the overall flow of a piece. They serve as critical navigational markers on the music staff, dictating each measure’s number and type of beats.

A time signature, typically placed after the key signature at the beginning of a piece, is displayed as two numbers, one atop the other, resembling a fraction.

The upper number denotes the number of beats per measure, while the lower number represents the note value assigned to each beat.

Consider the common 4/4 time signature, often termed “common time.” The upper “4” specifies that there are four beats in each measure, and the lower “4” indicates that the quarter note (1/4) gets the beat.

This means you could have four quarter notes, eight eighth notes, sixteen sixteenth notes, or any combination that doesn’t exceed the total beat count in each measure.

Similarly, a 3/4 time signature signals that each measure contains three beats, with the quarter note representing one beat – often recognized in waltzes.

An understanding of time signatures is crucial to both performance and composition. For performers, it offers insight into the rhythm and tempo, facilitating the accurate interpretation of the music. For composers, it provides a structural framework to guide the rhythmic organization of their musical ideas.

Time signatures can be simple (2/4, 3/4, 4/4) or compound (6/8, 9/8, 12/8), where the beat is divided into two or three equal parts, respectively.

There’s also the concept of “complex” or “irregular” time signatures like 5/4 or 7/4, which do not fit into the simple or compound categories and often lend a distinctive rhythmic profile to a piece.

Overall, time signatures impart a fundamental rhythmical structure to a piece, informing the performer about the beat pattern that frames the melody and harmony of the composition.

It is one of the vital components that help translate the dots and lines on a music staff into a musical performance.

We’ve touched on time signatures in this guide, but for a comprehensive understanding, check out our in-depth post on time signatures.

Music Staff in DAWs and Notation Software

In today’s digitally-driven music creation landscape, the music staff finds a new home within Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) and music notation software.

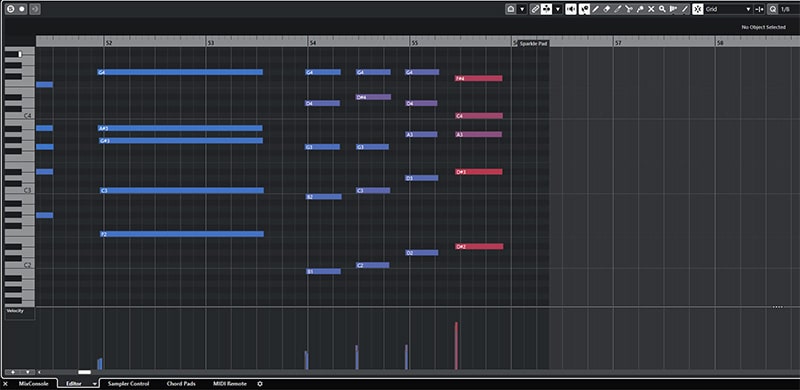

Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs), such as Logic Pro, Cubase, Ableton Live, and FL Studio, have a built-in “piano roll” or “MIDI editor.”

This feature visually represents music data on a grid-like staff, with time flowing left to right and pitch represented vertically, resembling a piano keyboard.

The piano roll allows for creating, editing, and visualizing MIDI data and is a crucial tool for any digital composer or producer.

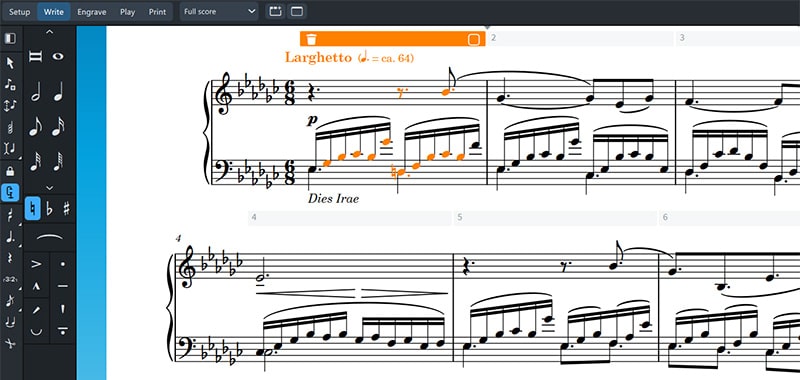

Music notation software, such as Finale, Dorico, and MuseScore, utilizes the traditional five-line music staff that musicians have been reading for centuries.

This software is essential for composers, orchestrators, and arrangers who need to create printable, legible sheet music for performers.

It allows users to input notes, rests, articulations, dynamics, and all the components of traditional music notation onto a digital music staff.

In these programs, the music staff serves the same purpose as traditional handwritten music. It facilitates the precise documentation of musical ideas, allowing them to be shared, interpreted, and performed by others.

While DAWs and notation software each offer their unique workflows, they both rely on the foundational concept of the music staff. Understanding how to read and navigate the music staff is an essential skill that translates directly into working effectively with these digital tools.

Moreover, many of these digital tools offer resources and tutorials to help beginners familiarize themselves with music notation. Learning to read music and learning to use music software go hand in hand, with each process enriching the other. Therefore, even in our digital age, the music staff remains an enduring, central component of music making.

Conclusion

The journey through the nuances of music theory, particularly focusing on the music staff, is both a fascinating and practical endeavor for every musician, songwriter, and producer.

We’ve explored the fundamental concepts of the music staff, including the lines and spaces, the clefs and their roles, and how they relate to pitch and musical notation.

We’ve also examined the integral relationship between the music staff and time signatures, highlighting how they shape rhythm and the overall feel of a piece.

Through the lens of Digital Audio Workstations and music notation software, we delved into the digital landscape, where the music staff plays an indispensable role.

Besides note symbols, many different symbols (ext. link) are used on the music staff.

Remember, mastering music theory and using the music staff is a continuous process; there are always new concepts to grasp, techniques to learn, and software to navigate.

Keep exploring, keep asking questions, and never stop expanding your knowledge.