Musical notes are the building blocks of sound in music, signifying pitch and duration. They form the foundation for melody, harmony, and rhythm.

Introduction

Musical notes, the building blocks of music, allow musicians to write, read, and create sound in a standardized language that transcends cultural and geographical boundaries.

This article is your starting point for understanding musical notes, whether you’re a beginner starting from scratch, an aspiring songwriter, a keen music producer, or simply a music enthusiast eager to learn.

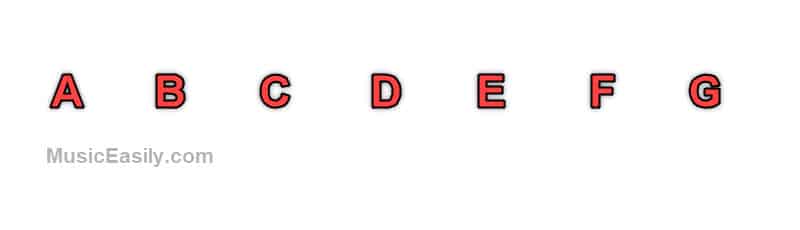

Musical notes communicate pitch – how high or low a sound is – and rhythm – the duration and timing of sounds. The Western music system recognizes seven primary notes: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. Their mastery and application lay the groundwork for creating diverse, mesmerizing music.

Understanding musical notes is vital. They shape melodies for songwriters, dictate actions for performers, and guide sound engineering for producers in digital audio workstations (DAWs).

Once you grasp the concept of notes in music, you’re well on your way to tackling more complex musical theory, like chords and scales, and even using music software more effectively.

Starting can seem daunting, but every great musician begins with the basics. Throughout this article, we’ll use visual tools like the piano keyboard and music staff to aid your understanding.

We’ll cover the essentials of musical notes, pitch, octaves, and the terminology of sharps, flats, and naturals. Additionally, we will delve into the concept of duration, or note values, which plays a vital role in accurately reading and interpreting sheet music.

By the end, you’ll have a solid understanding of musical notes and be ready to further your exploration and creativity in the world of music. Let’s begin!

Basics of Musical Notes

Diving into music theory, we’ll begin by establishing a foundational understanding of musical notes. Musical notes represent the pitch and duration of sound in music.

Pitch refers to the “height” or “depth” of a sound, telling us how high or low a sound is. Duration, however, tells us how long that sound is sustained. Mastering these two aspects of musical notes is crucial to articulate the music you wish to create accurately.

The Musical Alphabet

The pitch of a musical note in Western music is represented by one of the first seven letters of the alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. These seven letters form the basis of the “musical alphabet.”

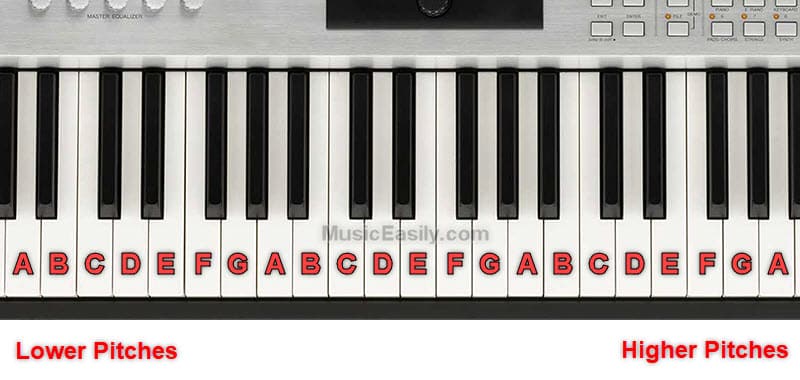

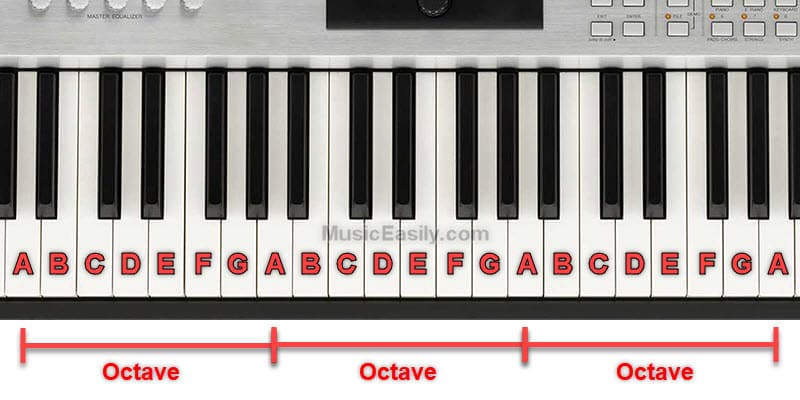

It’s important to note that the musical alphabet is cyclical. If you examine a piano keyboard, you’ll see that the pattern of white keys (A through G) repeats throughout the keyboard’s entire span, with each repetition representing an octave. After G, you circle back to A, but this new A is at a higher pitch.

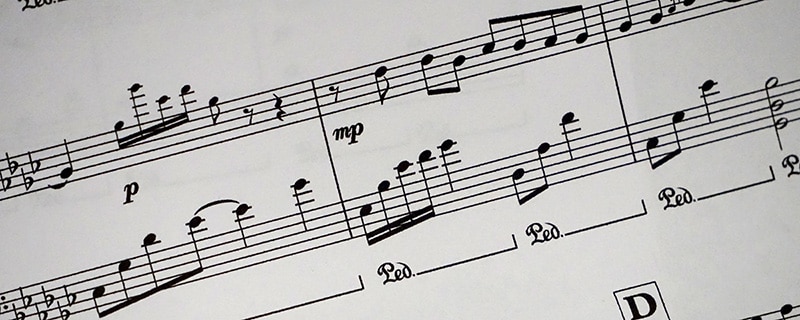

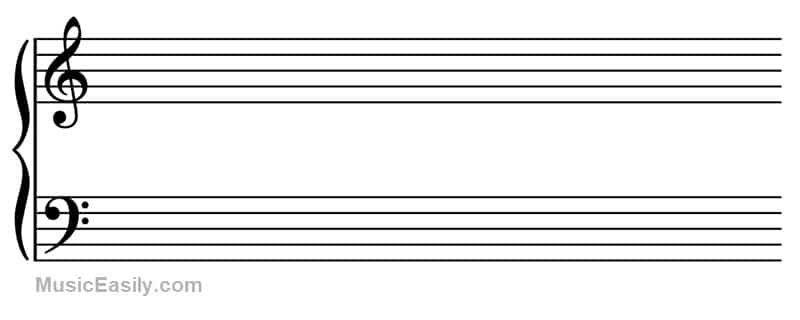

The Music Staff

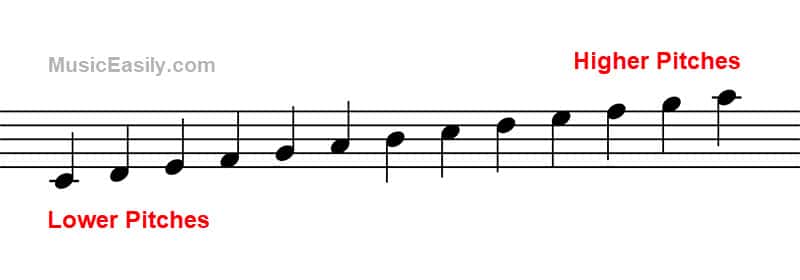

Music is typically written on a five-line grid known as a staff. The staff is the canvas where we draw our musical notes, dictating pitch and duration.

To understand how this works, imagine the lines and spaces of the staff as steps on a ladder. The higher a note is placed on the staff, the higher its pitch; the lower it is placed, the lower its pitch.

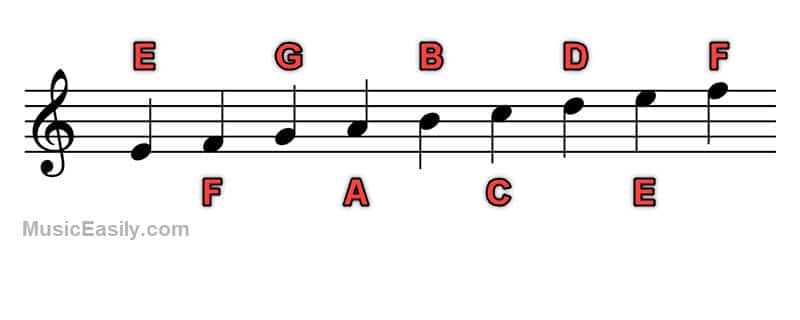

There are five lines and four spaces on every staff, and each line and space represents a different musical note.

In the most common staff notation, called the treble clef or G clef, the notes on the lines from bottom to top are E, G, B, D, F, often remembered by the mnemonic “Every Good Boy Does Fine.” The notes in the spaces spell out F, A, C, and E from bottom to top.

Ledger Lines

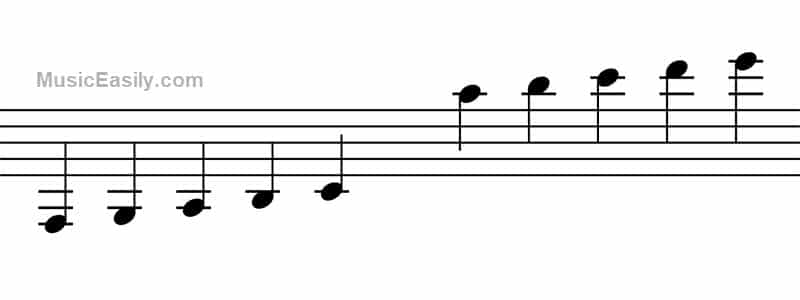

But what happens when a note is too high or too low to fit within the five lines of the staff? This is where ledger lines come in.

Ledger lines are short lines extending the staff to accommodate musical notes beyond the range of the five lines and four spaces.

If a note is higher than the top line of the staff, a ledger line is drawn above the staff to represent it. Similarly, if a note is lower than the bottom line, a ledger line is drawn below the staff.

We can represent a wide range of pitches using ledger lines, giving us flexibility in writing and reading music.

Remember, the staff and ledger lines guide the vertical position of notes, indicating their pitch.

As we explore further, we’ll discover how the horizontal placement of notes on the staff, combined with note values, provides a complete picture of a piece of music, depicting both melody (pitch) and rhythm (duration).

Note Values

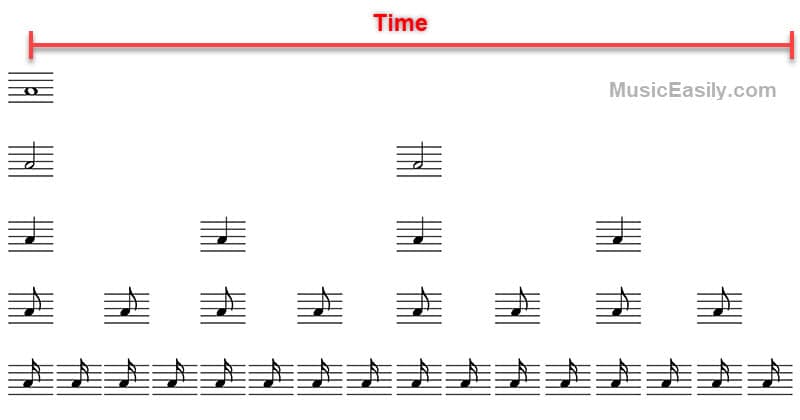

While the pitch of a musical note tells us its “height”, the note value informs us how long that note is held or sustained. This is an integral part of understanding rhythm and timing in music.

Below is a table showcasing the fundamental note values that are essential to understand.

| Note Name | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Note |  | Symbolized by an open oval, a whole note is typically the longest note duration in most time signatures |

| Half Note |  | Half the duration of a whole note, represented by an open oval with a stem |

| Quarter Note |  | A quarter of a whole note’s length, depicted as a filled-in oval with a stem |

| Eighth Note |  | An eighth of a whole note’s duration, represented similarly to a quarter note but with a single flag attached to the stem |

| Sixteenth Note |  | Sixteenth of a whole note’s duration, similar to an eighth note but with two flags on the stem |

These note values form the basic rhythmic building blocks of music, allowing the structuring of complex rhythms and musical patterns. Note that shorter note values (such as thirty-second and sixty-fourth notes) are used less frequently and will not be discussed in-depth in this beginner-oriented article.

The image below displays a comparative chart illustrating the relative durations of the note types we discussed.

Grasping the concepts of the musical alphabet and note values is a crucial stepping stone toward more advanced music theory topics. By understanding these basics, you’re well on your way to reading and writing music with greater fluency and ease.

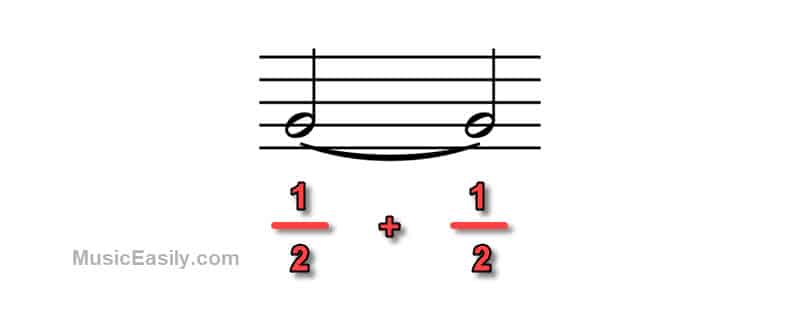

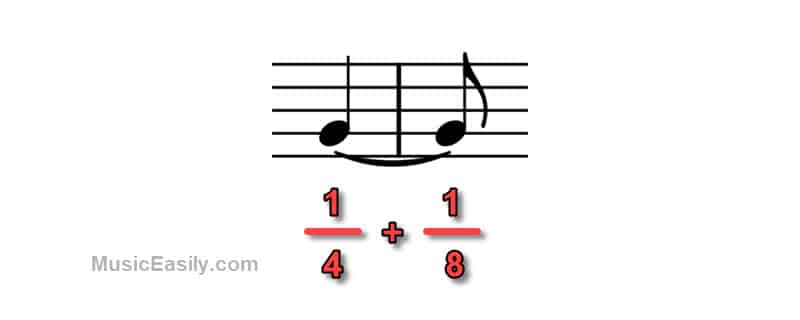

Ties

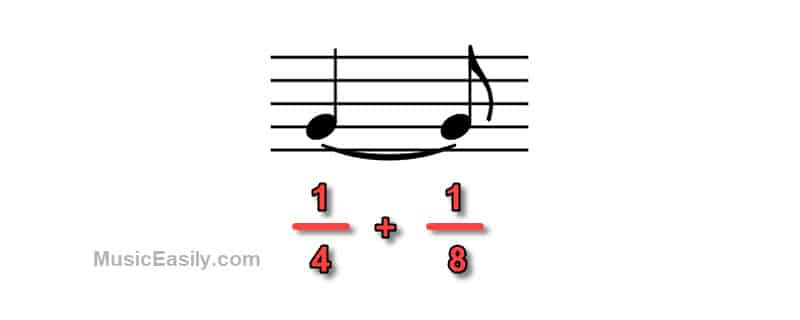

In music, a tie is a curved line that connects two notes of the same pitch, instructing the musician to play them as a single note with a duration equal to the sum of the original notes.

Ties allow composers to extend the duration of a note beyond its standard value, adding flexibility to rhythmic patterns. For instance, a quarter note tied to an eighth note would result in a note that lasts for three eighth beats.

Similarly, two half notes tied together would create a note that lasts for four beats, the equivalent duration of a whole note.

Moreover, ties can be used to extend the duration of a note into the next measure or even between lines and pages. This technique is beneficial when a composer wants a note to ring out longer than a single measure allows or to create sustained tones that transcend the limitations of measure lines.

It’s crucial not to confuse ties with slurs, another type of curved line in music notation. Slurs serve a different purpose – indicating that notes of differing pitches should be played smoothly or “legato.”

Importantly, if a curved line connects two or more notes of the same pitch, it’s considered a tie, not a slur. A more in-depth discussion on slurs and legato playing will be covered in a dedicated blog post on articulation.

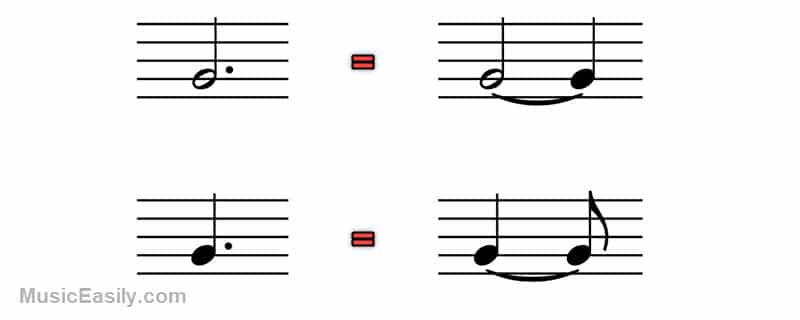

Dotted Notes

Adding a dot to a note also impacts its duration by explicitly increasing its original value by half. This means that a dotted note equals the note’s original duration plus half of that duration.

For instance, a dotted quarter note lasts as long as a quarter note plus an eighth note — effectively making it one and a half beats in 4/4 time.

This can be visualized as a quarter note tied to an eighth note, reinforcing the concept of ties we discussed in the previous section. Similarly, a dotted half note equals a half note plus a quarter note, totaling three beats in a 4/4 time signature.

Dotted rhythms are prevalent across all types of music, from classical to contemporary, as they allow composers to create interesting rhythmic variations. Recognizing dotted notes and understanding their values is key to interpreting and playing music accurately.

Rests

While our focus so far has been on musical notes, rests, the silent counterparts to notes, are equally important in shaping the rhythm and texture of a piece of music.

Like notes, rests come in different types, each signifying a different duration of silence. For example, a whole rest corresponds to a silence that lasts for four beats in 4/4 time, while a half rest lasts for two beats, and so on.

Although we’ve introduced the concept here, it’s worth noting that the topic of rests in music is broad and nuanced. We will dedicate a future article to a more comprehensive understanding of rests, their different types, and their role in music composition.

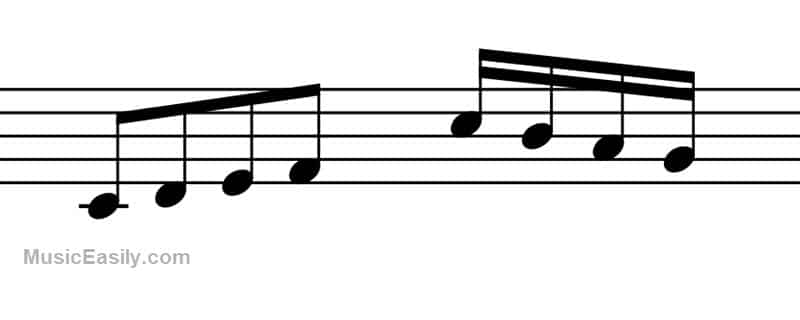

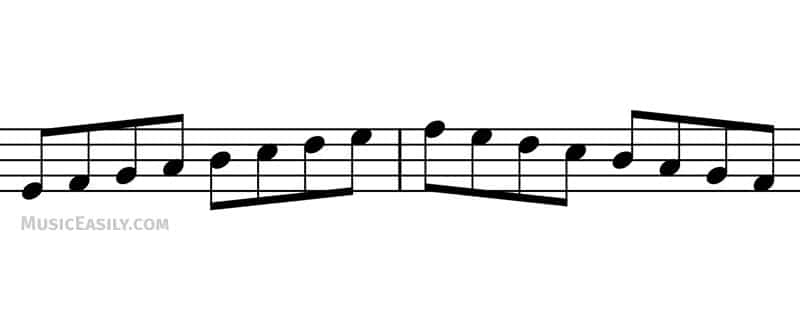

Beamed Notes

An important part of reading sheet music involves understanding how notes are grouped together. When we see two or more notes connected by a line or a “beam,” we look at beamed notes.

These beams connect eighth notes or shorter in duration, generally indicating notes that should be played together in a single beat or rhythmic unit. They provide visual cues that help musicians read music more quickly and accurately, especially in pieces with fast tempos or complex rhythms.

Consider this image. The beam connecting the notes makes it clear that these notes belong together as a rhythmic group. When notes are beamed together, the number of beams corresponds to the number of flags each note would have if it were not part of a group.

The first group of notes, all with a single beam, are eighth notes, and the second group of notes, each with two beams, are sixteenth notes. This indicates the rhythmic distinction within each group.

For example, when eighth notes are beamed together, they share a single horizontal beam. This mirrors the single flag of an individual eighth note when it is not part of a group. Similarly, when sixteenth notes are beamed, they will share two horizontal beams, reflecting the two flags of an individual sixteenth note.

Beaming rules can vary based on the time signature of the piece and the specific rhythm the composer wants to emphasize. However, a basic understanding of beamed notes is essential for reading and interpreting sheet music effectively.

As you become more comfortable reading sheet music, you’ll recognize patterns and rhythms within these beamed groups. This understanding will enhance your musical intuition and performance.

Also, remember that beaming isn’t exclusive to notes of the same duration. You’ll often encounter groups of beamed notes that include both eighth and sixteenth notes. In the next image, you’ll see examples of these mixed groups.

This understanding of rhythmic notation is only the beginning; there’s much more to learn as you continue your musical journey.

Stem Direction in Notes

The direction of a note’s stem can carry additional meaning in music notation. By convention, stems for notes on the middle line of the staff and above typically point downwards, while those for notes below the middle line point upwards. However, this is not an absolute rule and may vary depending on the musical context.

When multiple notes are beamed together, the group follows the stem direction of most of the notes. The stems usually point downwards if there’s an equal number of notes above and below the middle line.

This directionality aids readability and clarity, guiding the musician’s eye through the flow of the music. Understanding these conventions will help you read, write, and interpret musical scores more effectively.

As always, there can be exceptions based on the composer’s stylistic choice or specific requirements of the musical piece. It’s always best to combine these guidelines with reading different musical scores to understand the nuances of musical notation better.

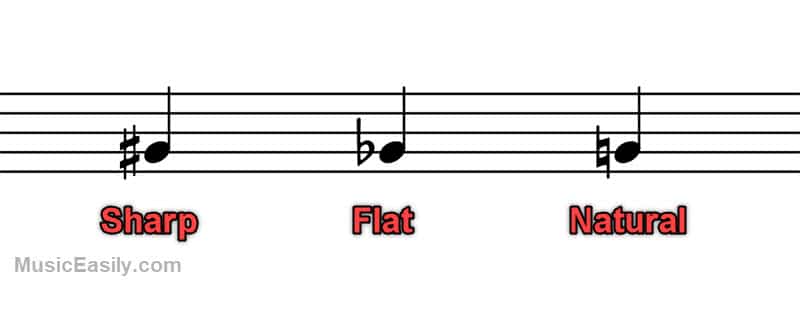

Sharps, Flats, and Naturals

In music notation, sharps, flats, and naturals are symbols used to alter the pitch of a note. These modifications can be vital in shaping the melody and harmony of a piece. Hence understanding them is a necessary stepping stone in your musical journey.

A “sharp” (#) raises the pitch of a note by a half step. Using a piano keyboard as a reference would be equivalent to moving one key to the right, whether white or black. For instance, a C# (C sharp) is one half-step higher than C.

Conversely, a “flat” (b) lowers the pitch of a note by a half step. On the piano, you would move one key to the left, whether white or black. So, a Bb (B flat) is one half-step lower than B.

A “natural” sign (♮) cancels a previous sharp or flat, restoring the note to its original pitch. For example, if you see a C# earlier in a measure and then see a C♮ (C natural), the C♮ indicates to play a standard C, not a C#.

The use of sharps and flats leads us to an interesting observation about the total number of pitches in the standard Western chromatic scale.

While the musical alphabet consists of seven letters (A through G), the total number of distinct pitches is 12. This includes the seven natural notes (A, B, C, D, E, F, G) and five additional pitches represented by the sharps or flats of these natural notes.

These additional pitches are A♯ (or B♭), C♯ (or D♭), D♯ (or E♭), F♯ (or G♭), and G♯ (or A♭).

The term “chromatic” comes from the Greek word “chroma,” meaning “color.” Thus, with its 12 pitches, the chromatic scale offers a full “color palette” of tonal possibilities in Western music.

Understanding Pitch and Octaves

Building on our foundational understanding of pitch and the musical alphabet, let’s delve further into how these elements interact within the structure of music.

The pitch of a sound refers to how “high” or “low” it is perceived. In music, pitch is represented by notes like “A,” “B,” “C,” etc. However, these pitches are not isolated – they are part of an interconnected pattern known as octaves.

An octave is a range of pitches from one named note to the next of the same name. For example, the pitch range from A to the next higher A is an octave, encompassing an eight-note pattern in the diatonic (major or minor) scale.

A specific pitch is typically denoted by its note name and octave number to convey its exact location in the musical spectrum.

Understanding the Keyboard Layout

A piano keyboard is an excellent tool for visualizing the concepts of pitch and octaves. The white keys correspond to the seven letters of the musical alphabet (A through G), with the cycle repeating every octave.

Interspersed among the white keys are black keys, grouped in sets of two and three. These black keys represent the enharmonic equivalents in music—notes that sound the same but have different names. For instance, the black key to the right of C can be identified as C# (C sharp), while the same black key is also Db (D flat) when considered relative to the D key.

The piano keyboard is anchored around the note C, which can be found to the left of each pair of two black keys. This note is significant because it’s the starting point of Western music’s most commonly used scale—the C Major scale, which comprises only the white keys and no sharps or flats.

Correlating Piano Keys and Staff Notes

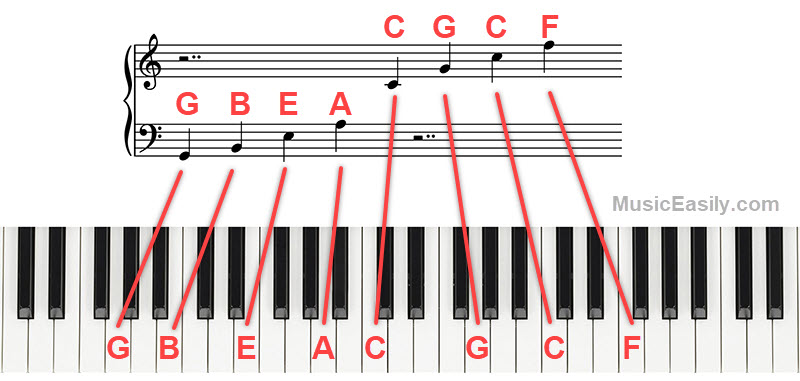

On sheet music, the Grand Staff, which includes the treble and bass clefs, represents the full range of pitches that can be played on a piano.

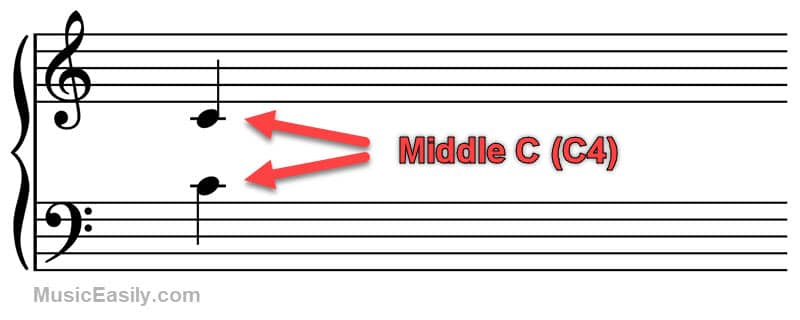

Middle C, designated as C4 in scientific pitch notation, corresponds to the C nearest to the center of the piano keyboard. This notation indicates the “C” note within the fourth octave on an 88-key piano, starting from the lowest octave. Middle C is notated on a short line known as a ledger line, positioned between the treble and bass clefs.

This is an application of the ledger lines concept we discussed earlier in the article, where musical notes that fall outside the staff are notated on additional short lines above or below it.

The image below illustrates how the same note, middle C, can be notated in two locations on the Grand Staff. As you can see, middle C can be written just below the treble clef or above the bass clef using a single ledger line.

The choice of where to notate middle C, like other notes that can be written on either staff using ledger lines, often depends on which hand the composer intends to play that note.

Typically, if the note is intended for the right hand to play, it would be notated on or near the treble clef, and if it’s for the left hand, it would be notated on or near the bass clef. These placement decisions not only provide clarity and readability for the musician but also extend the functional range of each staff.

In fact, ledger lines between the treble and bass staves of the Grand Staff are not limited to middle C. They can extend the range of each staff, enabling the notation of pitches typically associated with one clef on the other.

In the following illustration, we’ve marked several notes on the Grand Staff and their corresponding keys on a piano keyboard. It’s important to note that this graphic doesn’t represent all possible notes, but it offers a clear snapshot of how sheet music notation aligns with the physical layout of the keyboard.

You’ll also see how Middle C (C4) is denoted on the treble clef using a ledger line, affirming the concept of versatility in note placement within musical notation. This understanding is essential as it aids in efficiently reading sheet music and translating it to the keyboard.

Middle C Labeling Differences in Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs)

While middle C is consistently the same pitch across all platforms, its octave designation can differ depending on the software or hardware manufacturer’s chosen standard. For instance, Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) such as Cubase, Logic Pro, Ableton Live, or FL Studio might label middle C as C3, C4, or even C5.

This discrepancy can initially seem confusing, but it’s simply a labeling difference and doesn’t affect the actual pitch of the notes. What’s important is to familiarize yourself with the notation system used in your chosen DAW or keyboard. Whether labeled as C3, C4, or C5, the “C” closest to the middle of your keyboard or MIDI controller is universally recognized as middle C.

Reading Musical Notes

Reading musical notes on a music staff can be compared to unlocking a coded message. You’ll steadily decipher this musical code with patience and practice.

Firstly, identify the clef at the beginning of the staff. The most common are the treble and bass clefs.

In the treble clef, the notes on the lines from bottom to top are E, G, B, D, and F (EGBDF) — easily remembered by the phrase “Every Good Boy Does Fine.” The spaces spell out FACE from bottom to top.

On the bass clef, the lines represent G, B, D, F, and A (or “Good Boys Do Fine Always”), while the spaces represent A, C, E, and G (or “All Cows Eat Grass”).

When you see a note on a line or space, your task is to recognize it and understand how it corresponds to a key on your instrument. For piano players, this involves identifying the right key on the piano to play for a given note on the staff.

Practical Exercises

Now, let’s turn knowledge into action. Below are a few simple exercises to get you started:

- Flashcards: On one side of a card, draw a note on the staff. On the other side, write the note name. Use these flashcards to practice identifying notes.

- Sheet Music: Try to read simple sheet music. Start with pieces that use one clef with few accidentals (sharps or flats). Gradually progress to more complex pieces.

- Write It Out: Practice writing the notes yourself. Choose a random note and try to write it correctly on the staff. This exercise helps reinforce your understanding of note placements.

- Play and Say: Say the note names aloud while playing a piece. This exercise can help reinforce the connection between the note on the page and the physical act of playing it.

Remember, progress may be slow initially, but consistency is critical. Over time, you’ll find your reading speed and comprehension improving. Keep at it, and soon, reading music will become second nature.

Conclusion

To summarize, we explored the basics of music theory, starting with music staff and ledger lines, moving on to pitch and octaves, and understanding enharmonic equivalents. We also visually mapped musical notes using a piano keyboard layout.

We then delved into the nuances of sharps, flats, and naturals. Reading musical notes and practical exercises were also covered, allowing beginners to put theory into practice.

For a comprehensive catalog of the various symbols you’ll encounter as you deepen your understanding of music notation, refer to this article on the list of musical symbols (ext. link).

Remember, learning music theory is a journey that requires patience and practice. Keep exploring and creating.