Accidentals in music are symbols that alter the pitch of a note, making it sharp, flat, or natural. They play a key role in shaping melody, harmony, and the overall expressive quality of a piece.

Introduction to Accidentals in Music

If you’ve spent time learning or reading music, you’ve likely encountered these small symbols—sharps, flats, and naturals—that pop up alongside your notes.

These are called accidentals, the secret ingredients that give music distinctive flavor and color. Even the simplest tunes can transform dramatically with just a pinch of these powerful symbols.

At the most basic level, accidentals in music are symbols that alter the pitch of a note. When we speak about pitch, we’re referring to the perceived frequency of a sound – whether it sounds high or low.

In music notation, there are five main types of accidentals, including the sharp (♯), flat (♭), natural (♮), double sharp (𝄪), and double flat (𝄫). These symbols alter the pitch of the notes they precede, adding depth and complexity to the musical composition.

But music accidentals do more than tweak pitches. They profoundly impact the mood, emotion, and narrative of a piece of music. You can think of them as the spice in your musical curry, the plot twist in your favorite novel, or even the curveball in a baseball game.

Take a blues song, for example. The raw, soulful character of the blues owes much to its frequent use of flattened notes—what we musicians call “blue notes.” Or consider the tension and resolution in classical composition, often engineered by the clever use of sharps and naturals.

In essence, accidentals are the tools composers and songwriters use to create tension, resolution, surprise, and emotional depth in their music.

Accidentals also follow specific rules and conventions in written music, which we’ll explore in this article. They are essential for defining key signatures, constructing scales, and influencing harmonic progressions.

By the end of this comprehensive guide, you will be familiar with the nuts and bolts of accidentals and appreciate their musical power and significance.

Understanding Accidentals

When exploring the realm of accidentals, the most common and fundamental symbols encountered are the sharp (♯), the flat (♭), and the natural (♮). Each symbol plays a vital role and holds substantial importance in music.

It’s crucial to remember that in the case of accidentals placed before individual notes, these symbols only affect the note they’re directly in front of for the remainder of the measure. After that, the notation returns to the defaults set by the key signature unless another accidental appears.

This rule, however, does not apply to the accidentals within the key signature, which consistently affect their designated notes throughout the piece.

Sharps and Flats

Sharps and flats are fundamental in the world of accidentals. They’re responsible for adjusting a note a half step up or down.

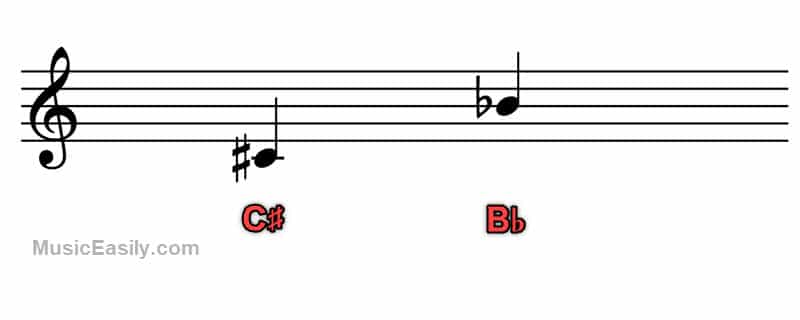

A sharp (♯) symbol tells you to raise a note by a half step. For example, if you see a sharp before a “C” note (C♯), you’re to play a pitch one half step higher than C. It’s like going up one stair on a staircase, from one step to the very next one.

A flat (♭), on the other hand, is the opposite of a sharp. It lowers a note by a half step. So if you’re faced with a “B” flat (B♭), you’d play a pitch that’s one half step lower than B. It’s like going down one stair from your current step.

Naturals

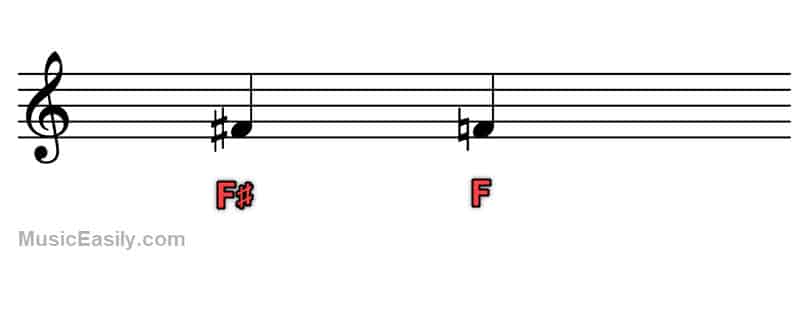

Natural signs (♮) serve as a reset button in music accidentals. They revert a note’s pitch to its original, unaltered state by canceling the effects of sharps or flats. When you see a natural sign in sheet music, it’s a directive to play the note at its original pitch, free from any alterations made earlier in the measure.

Suppose you’ve been playing an F# in a measure, and the composer wants you to return to the standard F within the same measure. The composer won’t just write an “F” without any accidental, because according to the rules of music notation, you’d still play it as F# because of the previous sharp in the measure.

Instead, they’ll add a natural sign before the “F” to indicate the correct pitch. This clarifies that they’re requesting a natural F, not an F#. Once a natural sign is placed before a note, it resets that note to its original pitch for the rest of the measure.

Remember, these rules reset at the beginning of each new measure. If a note was altered with an accidental in one measure, that alteration doesn’t carry over to the next measure unless it’s marked with another accidental. This is why you might often see the same accidental used repeatedly in a piece of music.

Double Accidentals

An extension to sharps and flats exists in music notation, known as double sharps (𝄪) and double flats (𝄫). These accidentals represent a further pitch modification, albeit less frequently used than their single counterparts.

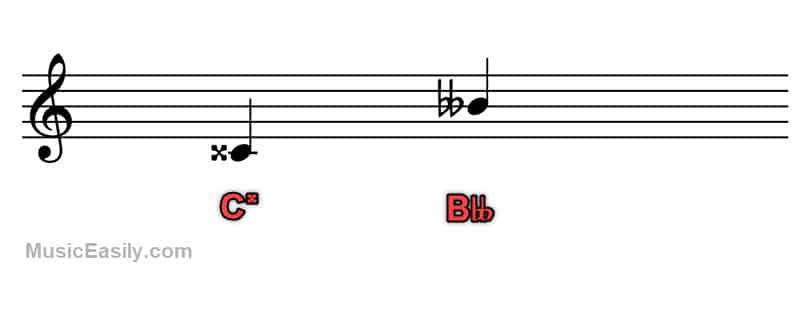

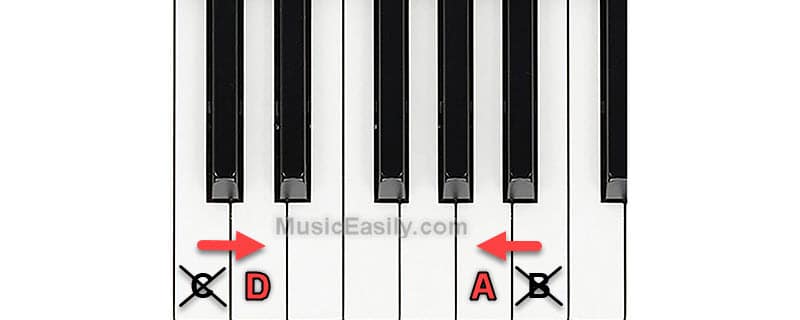

A double sharp, denoted by the symbol 𝄪, raises the pitch of a note by two half steps, equivalent to a whole step. Consequently, a note such as C𝄪 would be played two half steps higher, correlating to the pitch commonly associated with D. However, in the given musical context, it remains crucial to interpreting the note as C𝄪, despite its auditory equivalence to D.

Contrarily, a double flat, represented by 𝄫, lowers the pitch of a note by two half steps. Therefore, a note like B𝄫 directs the performer to play a whole step lower, correlating to the pitch typically known as A. But within the theoretical construct of the piece, this pitch should be treated and referred to as B𝄫.

Double accidentals may seem counterintuitive, especially when they result in pitches commonly referred to by another name. Nonetheless, they play an essential role in preserving the theoretical consistency of a piece.

Now that we’ve covered the basic and some extended accidentals, let’s take a look at a quick overview. Below, we have a table that outlines these accidentals and their respective effects on pitch:

| Accidental | Symbol | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Sharp | ♯ | Raises the pitch of a note by a half step |

| Flat | ♭ | Lowers the pitch of a note by a half step |

| Natural | ♮ | Restores a previously altered note to its original pitch within the same measure or cancels out the effect of a sharp or flat specified by the key signature |

| Double Sharp | 𝄪 | Raises the pitch of a note by two half steps (equivalent to a whole step) |

| Double Flat | 𝄫 | Lowers the pitch of a note by two half steps (equivalent to a whole step) |

These accidentals can be found in all genres and styles of music. Their usage and effect can be more nuanced in practice, due to their interaction with the key signature, the context within a melody or harmony, and other factors.

Accidental Rules and Conventions

As with any musical notation, the use of accidentals adheres to a set of conventions and rules, each serving a crucial purpose in ensuring consistency and clarity. Understanding these rules will improve your fluency in reading and writing music.

Scope Within a Measure

First and foremost, an accidental’s scope is limited to the measure it appears in and only affects the note it precedes. In other words, an accidental will alter the pitch of a note for the rest of that measure, but once you cross the bar line into the next measure, its effect is nullified.

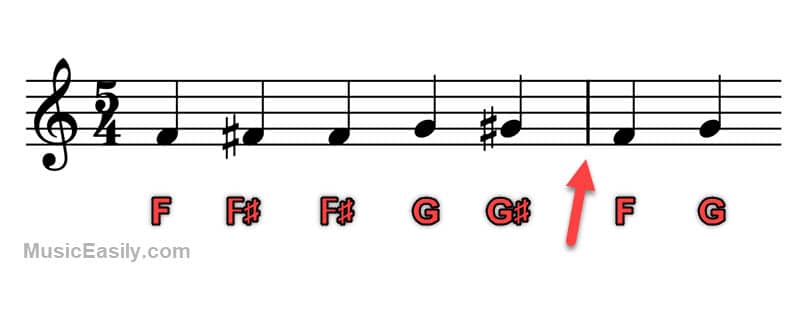

Consider a measure in a piece of music written in the key of C Major, which has no sharps or flats.

This measure contains the notes F, F#, F, G, and G#. In this case, the first F would be played at its natural pitch. The second note, F#, indicates that you should raise the pitch of F by a half step. The third note, another F, would still be played as an F# because of the previous sharp in this measure. The G would be played at its natural pitch. The final note, G#, instructs to raise the pitch of the G by a half step.

Now, if the next measure begins with an F and a G, these notes should be played at their natural pitches, even though they were altered in the previous measure. The effect of the sharp accidentals does not carry over to the next measure. Hence the scope of an accidental is within the measure it appears in.

Scope in Key Signatures

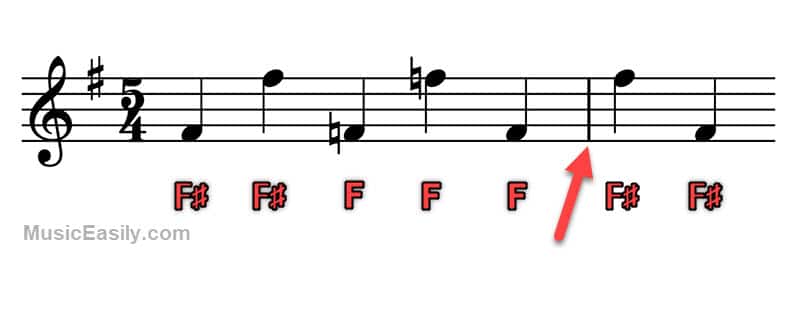

When accidentals are part of a key signature, they command a broader scope than those placed before individual notes. In this case, the accidentals apply to all corresponding notes throughout the piece across all octaves. This means if a key signature has an F#, every F note in the piece, regardless of its octave, is played as F#.

However, this rule can be overruled by accidentals placed directly before individual notes within a measure. These modifying accidentals affect only the specific note they precede, altering the key signature for that note within that measure alone.

The “Courtesy” Accidental

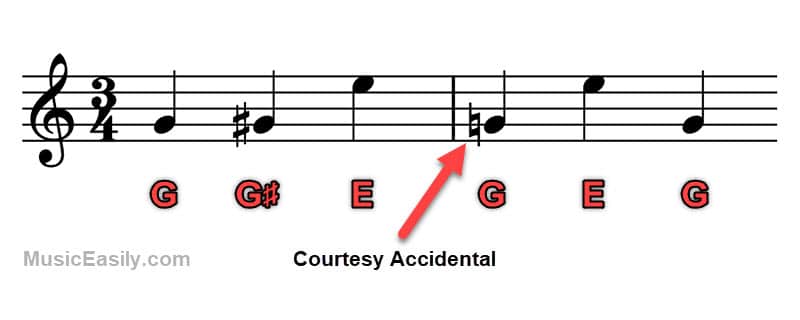

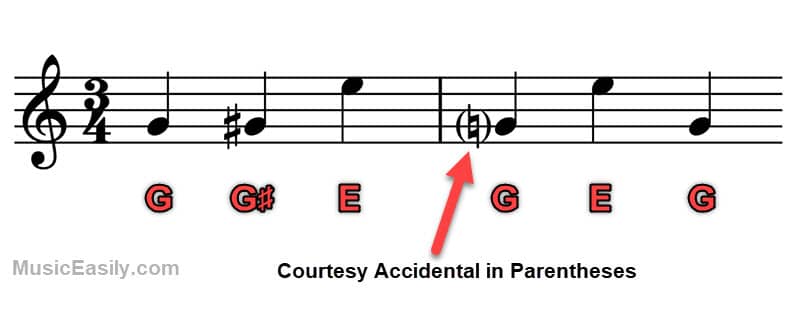

The “courtesy” accidental, also known as a cautionary or reminder accidental, is an instance where an accidental is used even though it’s not strictly necessary according to the rules. Typically, it’s used to confirm the pitch of a note following a measure where its pitch was altered by an accidental.

For instance, if a G note is raised to G# in one measure, and the following measure contains a G natural, placing a natural sign (♮) in front of the G in the second measure is common practice, even though it’s technically redundant. This acts as a gentle reminder to the performer and ensures clarity.

Courtesy accidentals can often be found in parentheses to make it clear that they’re serving as a reminder rather than indicating a change in pitch within the measure. For example, if you see “(♮)G” at the start of a measure, it’s a courtesy reminder that the G is to be played at its natural pitch, even if it had been altered in the previous measure.

These are particularly useful in complex pieces of music where many accidentals are in play, aiding the performer in maintaining the intended pitches.

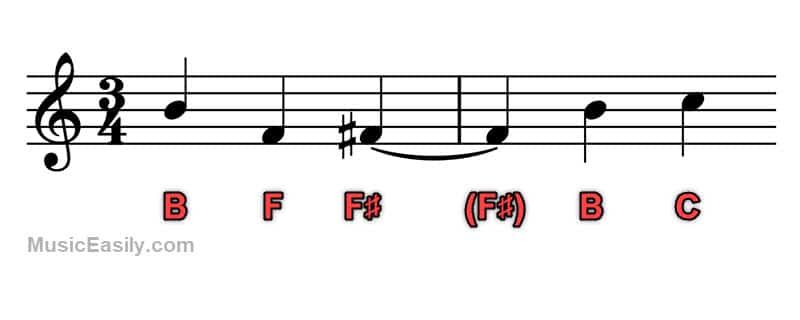

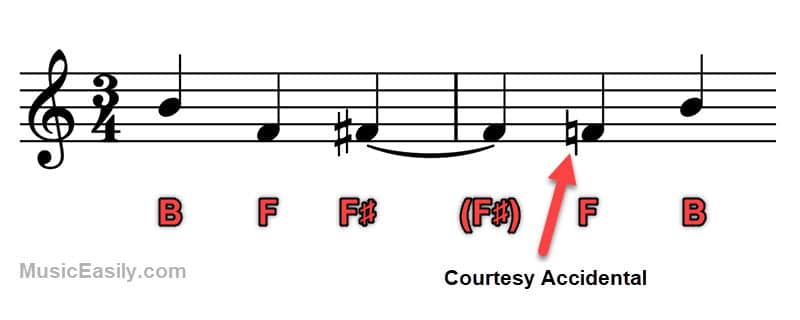

Accidentals and Ties

When a note altered by an accidental is tied to the same note in the next measure, the accidental continues to affect the tied note. It’s as if the tied note is an extension of the original, and the boundary of the measure does not disrupt the accidental’s influence.

If another note of the same pitch follows the tied note in the new measure, a courtesy accidental might be added to ensure the performer is clear on the intended pitch. This illustrates how courtesy accidentals can also be useful in the context of tied notes across measures.

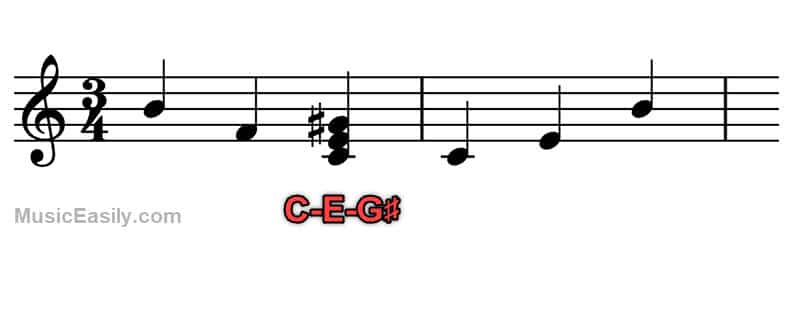

Accidentals in Chords

If an accidental is applied to a note that is part of a chord, it only affects the line or space the accidental is placed on and not the entire chord. For example, if you have a C Major chord (C-E-G) and add a sharp to the G, you get a C augmented chord (C-E-G#), not a C#-E#-G#.

Remember, these rules exist to streamline the notation process, remove ambiguity, and enhance communication between the composer and performer. Understanding and following these conventions is key to accurately conveying your musical ideas.

Enharmonic Equivalents

An integral part of understanding accidentals, and indeed music theory in general, is coming to terms with enharmonic equivalents.

Introduction to Enharmonic Equivalents

Simply put, enharmonic equivalents refer to two musical elements that are different in notation but identical in pitch. In the context of accidentals, they’re often the result of a note being raised or lowered by a half step, landing on a pitch that a different note name can represent.

The concept of enharmonic equivalents shines a light on music’s intricate, complex nature, pointing to the multifaceted ways we can understand, interpret, and articulate the sounds we make.

Examples of Enharmonic Equivalents

Let’s look at some common enharmonic equivalents you’ll frequently encounter. For instance, F# and Gb are enharmonic equivalents – they are different in notation but sound the same. Similarly, C# and Db are also enharmonic equivalents.

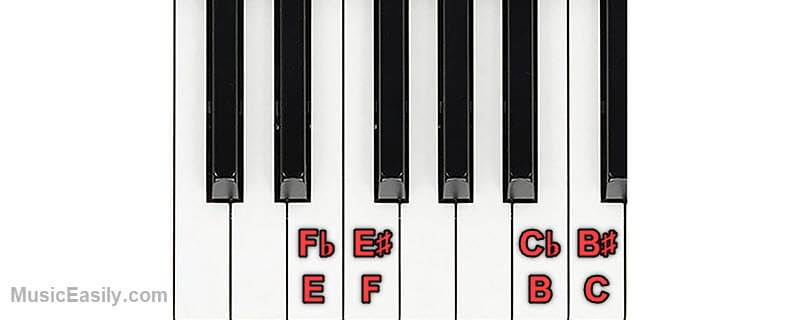

It’s not just about the black keys on a keyboard. Even notes that are naturally a half step apart can have enharmonic equivalents.

Consider the notes E and F or B and C. These notes are adjacent on a keyboard, with no black key (sharp or flat) between them. However, E might be notated as Fb, its enharmonic equivalent in certain musical contexts.

Similarly, F can be notated as E#, B as Cb, and C as B#. These seem like unusual notations, but they’re valid and have their uses in specific musical contexts.

With double accidentals, things can get more complex. A note such as F𝄪 (F double sharp) is enharmonically equivalent to G, and D𝄫 (D double flat) is enharmonically equivalent to C.

Practical Applications

Understanding the notion of enharmonic equivalents extends beyond merely demonstrating one’s music theory proficiency; it carries substantial practical implications.

As a composer or songwriter, understanding enharmonic equivalents opens up many possibilities for creating innovative harmonic progressions. For instance, this concept depends on enharmonic modulations, where one chord is reinterpreted as another to facilitate a key change.

For performers, particularly those playing fretted or keyboard instruments, recognizing enharmonic equivalents helps to navigate the instrument more efficiently. Similarly, music theorists use enharmonic analysis to understand and explain complex harmonic structures.

Limitations and Considerations

However, it’s important to remember that while two notes may be enharmonic equivalents, they are not interchangeable in all circumstances. The context, including factors like the key signature and chord progression, heavily influences how a note functions in a piece of music.

For instance, let’s consider a piece written in the key of Db Major. Here, Db is the tonic or home note of the scale. But if we were to notate this note as C#, it might be unclear to a musician familiar with key signatures and scale structures, as C# doesn’t naturally occur in the key of Db Major.

This example illustrates how Db and C# may be enharmonic equivalents and sound the same when played, but their notation and function can differ depending on the musical context.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s much more to learn and explore about enharmonic equivalents.

The Role of Accidentals in Musical Context

Understanding accidentals in music is more than just familiarizing oneself with their individual properties. Their real importance lies in their application within the fabric of music.

In this section, we will explore how accidentals contribute to the overall context of a piece, affecting everything from the key signature to the melodic and harmonic movements.

Accidentals and Key Signatures

Key signatures fundamentally determine the tonal structure of a piece by prescribing a group of sharps or flats. The presence of these sharps or flats informs us about the tonal center or key of the music. For instance, a key signature with an F sharp implies a tonal structure of G Major or its relative minor, E minor.

In our article on the Circle of Fifths, you can see the systematic sequence in which accidentals are added to each key signature. This visual representation can aid in understanding the structure and relationship of different keys in music.

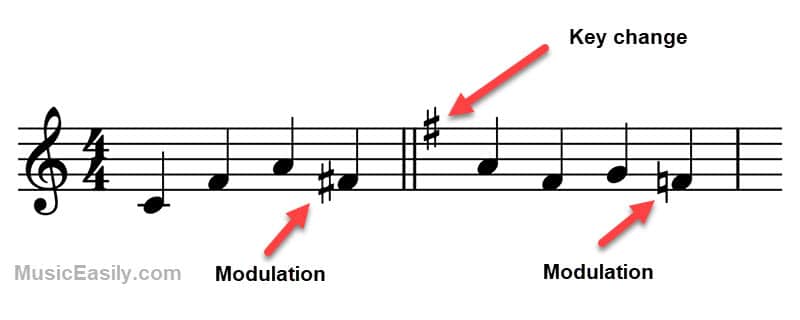

Moreover, a key signature isn’t static – it can change in the middle of the piece, signifying a modulation or key change. This underscores the dynamic role of accidentals in shaping the tonal landscape of the music.

Consider a piece of music that starts in the key of C Major, which has no sharps or flats. Let’s say the piece has a melody that, after a few measures, starts to include an F#. This accidental signals a temporary modulation to the key of G Major, which has an F# in its key signature.

In the middle of the piece, you might see a key signature change from no sharps or flats (C Major/A minor) to one sharp (G Major/E minor), indicating a complete key change, not just a temporary modulation.

At this point, unless indicated by an accidental, all F notes would be played as F# according to the new key signature. If a specific measure included an F natural, it would signify a temporary return to the tonal landscape of the original key (C Major) within that measure.

Chromatic Movement

Accidentals serve as an expressway to chromatic movement, a concept referring to melodic or harmonic motion by half steps. By raising or lowering pitches by half steps, accidentals enable composers to deviate from the diatonic scale notes associated with the key, creating an expansive palette of tonal colors.

A melody embellished with chromatic notes can evoke a sense of tension, drama, or surprise, enhancing its expressive potential. Similarly, a harmony enriched with chromatic movement can add complexity and depth. For instance, the colorful chords often used in jazz heavily rely on accidentals for their characteristic richness.

Whether it’s the bluesy charm of a flat five, the tension of a raised fourth, or the surprise of a flattened third in a major key, chromatic movement brings a distinctive flavor to music.

Influence on Intervals and Scales

Accidentals possess a transformative quality in music, allowing musicians to alter the sound texture. Their influence notably extends to intervals and scales, essential aspects of musical composition.

Let’s delve into how accidentals modify intervals and contribute to constructing various scales.

Modifying Intervals

Intervals represent the distance between two pitches and are a foundational element of music theory. When applied to a note within an interval, an accidental can alter its size, potentially resulting in augmented, diminished, or minor/major intervals, depending on the context.

Consider a Major Third interval (such as C to E). If the E is raised by a sharp (#), we end up with C to E#, effectively increasing the interval size and creating an augmented third. Alternatively, if the same E note is lowered by a flat (♭), the interval becomes a minor third (C to E♭).

These alterations play a significant role in changing the character of your melody or harmony, underlining the importance of understanding how accidentals interact with intervals. For a more detailed discussion on this topic, refer to our previously published post on intervals.

Constructing Scales

Scales, the series of notes that span an octave, provide the framework for melody and harmony in music. They are, in essence, a sequence of intervals. Accidentals can add variety to these scales, permitting the creation of diverse tonal structures.

Consider the major scale, which follows the pattern of whole and half steps: W-W-h-W-W-W-h. Applying accidentals to certain notes can transform this scale into a completely different one, such as the minor scale with the pattern W-h-W-W-h-W-W.

More complex scales, such as the harmonic minor or the melodic minor, heavily rely on using accidentals for their unique tonal qualities. The same goes for modes, essentially scales derived from the major scale.

In constructing these scales and modes, accidentals prove to be a powerful tool, offering countless possibilities in musical expression. For more information on scales and modes, refer to our dedicated blog posts “What is a Musical Scale?” and “What are Modes in Music?.”

Understanding the impact of accidentals on intervals and scales is one of the keys to mastering the art of music theory, composition, and songwriting.

Impact in Music Composition and Songwriting

Accidentals play a significant role in music composition and songwriting, shaping the character of melodies, enriching harmonies, and driving key modulations. By judiciously utilizing accidentals, a composer or songwriter can create a wide range of emotional effects, making the music resonate with the listener on a deeper level.

Adding Color to Melodies

In melody writing, accidentals are critical for creating expressiveness and diversity. By introducing sharps or flats not present in the key signature, composers can venture beyond the confines of the diatonic scale, adding unexpected color and nuance.

This technique often finds use in blues and jazz, where “blue notes” (flatted thirds, fifths, and sevenths) add a distinctive flavor. It also plays a significant role in pop and rock, where occasional accidentals can make a melody more catchy and memorable.

Enriching Harmonies

Harmonically, accidentals are integral in creating tension and resolution, a fundamental principle in Western music. By altering chords using sharps or flats, songwriters can introduce dissonance, which, when resolved, provides a sense of musical satisfaction to the listener.

Furthermore, accidentals can also allow for smooth chord progressions through chromatic voice leading, where one or more voices move by a half step to the next chord.

Modulating to a New Key

As explored in the previous section, “Accidentals and Key Signatures,” accidentals play a significant role in facilitating key modulation. This technique involves transitioning from one key to another within a piece, and it’s an essential tool for composers seeking to imbue their work with additional layers of interest, contrast, and emotional resonance.

Key modulation, mediated by the strategic use of accidentals, is a hallmark of many musical genres, particularly classical music and film scoring. It is effectively used to underscore varying scenes, moods, or thematic elements, adding a rich dimensionality to the music’s narrative arc.

Exploring Different Genres and Styles

The creative use of music accidentals is not limited to any genre or style. From the chromatic explorations in classical compositions and jazz improvisations to the evocative use of blue notes in blues and rock to the deliberate dissonance in some forms of avant-garde and experimental music, accidentals can be a gateway to new sonic possibilities.

Conclusion

Accidentals, though simple in appearance, play a substantial role in music theory, composition, and songwriting. They influence key signatures, enable chromatic movement, modify intervals and scales, and follow certain rules within a measure.

In composition and songwriting, they serve as potent tools to enhance expressiveness, create tension and resolution, and allow exploration of diverse genres. To further appreciate the evolution and application of accidentals, delve into this Wikipedia page about the fascinating history of well temperament tuning systems (ext. link).

Leveraging accidentals effectively can make your music stand out, resonating deeply with your audience. It’s a catalyst for creative freedom and expression. Understanding their function is more than merely theoretical. Mastering accidentals is a stepping stone in your unique musical journey.